Planning for evaluation I: Basic principles

You are in an archived section of the AIFS website

Introduction to the process

In conducting an evaluation, you are attempting to understand whether the program has achieved what you intended, and whether the changes in the participants can be said to be a result of the program rather than other factors that you did not, or could not, take into account. The degree to which these goals can be achieved is influenced by the rigour of your evaluation. A rigorous evaluation is one that is well-planned, takes as many non-program factors into account as possible, uses methods appropriate to the program objectives and the available resources, collects the best possible data, closely follows the established procedures, and so on.

In a nutshell, evaluation starts with a question. For example:

- Does your outreach program improve the quality of your clients' lives?

- Do new parents benefit from your parenting education program?

- Has the new model of supervision you implemented improved job satisfaction among your staff?

In order to answer your particular questions, you as an evaluator will need to work through a series of inter-connected and overlapping steps (see Box 1). While there is a generally linear sequence to the process, there are many smaller steps along the way, and many tasks that need to be managed in parallel. They each need to be carefully considered, a decision made as to whether action is needed, and the appropriate action taken. If you miss some of these steps, or don't allow enough time and resources to deal with them, you can find yourself taking two steps forward and one step back, or stalling the evaluation completely - and both the integrity of your evaluation and your timeline may suffer.

In this resource, we cover the key concepts, principles and terms relating to the broad stages of evaluation:1

- writing program objectives;

- program logic models;

- evaluation designs; and

- methods of data collection.

Box 1: Steps in an evaluation

The broad steps in an evaluation include:

- describing in detail the program, its objectives, and how its components lead to its intended outcomes;*

- formulating evaluation questions;

- deciding which measures or methods will be able to provide the data to answer the question(s);

- deciding how to collect that data and putting in place the procedures that will allow the data to be collected;

- collecting and analysing the data; and

- interpreting and acting on the findings.

* In a moderately ideal world, these particular tasks would have been completed at the time the program was being developed. In an even more ideal world, an evaluation plan would also have been written at the time the program was being developed.

Program plan and objectives

When seeking financial support for a program, potential funding bodies will want to know what benefits are expected for clients and how you will know that those outcomes have been achieved. In short, they will want to know details such as why the program is needed, who is the target audience, what resources are needed, and what will be the outcomes. Hopefully, your program would have been designed around a program description that includes these elements.

Having your program clearly documented - down to the specific theories or approaches used (e.g., attachment theory, social learning theory, public health approach, emotion-focused parenting approach), the research that informs what you do and say, and the rationales for particular methods and activities you use - will make setting up and implementing your evaluation much easier. A good evaluation rests on clearly articulated program objectives, so sufficient time needs to be allowed for these to be well thought out and specified.

What is a program objective?

A program objective2 is a specific statement of what the program is expected to achieve - what might be expected to change for the client as a result of their participation in the program. It needs to be obvious from the objective, for example, what behaviour or attitude you are hoping to influence, what knowledge and skills you hope participants will learn, or what aspect of the participants' lives you are hoping to improve.

Some things to think about regarding objectives:

- Objectives must be measurable or quantifiable in some way. Sometimes this will be quite obvious. For example, if you wanted to gauge improvement in a child's reading ability, this could be measured objectively by counting the number of words a child reads correctly in a given passage. Other objectives, however, may require evaluation by more subjective measures. Relationship quality, for example, may be measured by independent ratings of a couple's interactions on dimensions known to be associated with "good" relationship "functioning", such as constructive communication styles. It may also be measured by a simple set of questions asking how the partners feel about the relationship - how happy they are, how committed they are to the relationship, etc.

- Objectives may relate to rather complex things. For example, you may have developed a program to improve couple relationship functioning. "Functioning" is a complex concept that might include how couples communicate, argue, share activities, show affection, manage their finances, and so on. Do you try to measure each of these aspects of functioning, or just one or two? Which ones? Whatever is decided, the rationale must be explained in the evaluation report.

- Writing objectives can sometimes be rather tricky because some constructs cannot be measured directly. As an example, one of the things you might want your program to do is raise participants' insights into the impact of their gambling behaviour on family members. "Insight" is a concept that does not lend itself readily to measurement. How can you know that a participant has better insight after the program than they had before? Objectives that relate to broad concepts such as "insight" or "functioning" can only be inferred from information about changes in attitude or behaviour that reflect insight, or in the dimensions that contribute to the broader functioning of the relationship.

- Some cultural or ethnic groups may have a different understanding of a particular aspect of their lives that you need to measure. An Indigenous Australian's understanding of "family", for example, is more complex than many non-Indigenous Australians, so your objectives may need to be framed accordingly.

- To further complicate things, your program may have several specific objectives, each able to be assessed by one or more measures. For instance, a program that is designed to enhance resilience in adolescents might have a set of objectives that includes raising self-esteem, enhancing social support networks, improving body image, setting boundaries on relationships, learning new coping strategies, and so on. It is likely that there are at least two ways to measure or assess each of these. The number and quality of sources of support, and ease of access to and level of trust in each, for example, might be used to assess social support. The number of social supports can be thought of as a rather broad measure, whereas the level of trust in each source of support is a more fine-grained measure that provides considerably more information about the adolescent's social environment. You may have the resources to measure all of these or only one of them, so part of the process of setting up your evaluation will involve sorting out what, realistically, you can and cannot assess.

- Spending time on clearly setting out your program objectives will also make much easier the critical task of selecting the specific tools you will use to assess your objectives.3

- Objectives may be client-focused or directed at the agency or organisation itself. For example, some objectives refer to the outcomes intended for the participants in a program - the skills (e.g., parenting skills to help manage children's behaviour) or behaviours (e.g., gambling, substance use) of concern. Others might refer to an organisational goal,4 for example, of increasing the number of clients from a particular population such as those from a particular ethnic background, or reducing the rate of staff turnover.

Writing clear, measurable objectives

It can be helpful to start writing your objectives so that they complete the sentence: "By the end of this program/session, [the participant/client] will ...". The objective might refer to specific knowledge or skills that they might gain, to attitudes or behaviours that might be modified, or to aspects of their personality, physical or emotional wellbeing, or performance that might change. A useful aid to writing objectives can be found in the acronym SMART:

- Specific - state the "who" and "what" of each of the program activities, and focus on only one action; for example, at the end of the program participants will be able to identify or name good parenting techniques for toddler tantrums, or describe the indicators for suicidal behaviours.

- Measurable - indicate how much change is expected; for example, participants will be able to identify all four good communication techniques taught in the program, or a second objective might be that participants provide at least one example of the behaviour associated with toddler tantrums.

- Achievable - the objective needs to be one that is capable of being reached with a reasonable amount of effort and application; you need to make sure that you have given sufficient information about good parenting techniques for toddler tantrums during the program to allow both their identification and description.

- Realistic - the objectives must be set at a level that participants can realistically achieve given the time and resources available to them; in the context of a relationship education program, setting an objective of naming good communication techniques is more realistic than requiring them to write an essay about them.

- Time-based - your objectives need to be set within a defined timeframe as these help to provide motivation and prompts action on the part of the participants; in a program setting, your objective might specify that participants are expected to be able to identify the three strategies for taming toddler tantrums by the end of that session, or by the end of the program.

There are a number of additional SMART terms that can be used to assist with the writing of your objectives. The expanded version provides greater scope to write objectives applicable to a particular program (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Haughey, 2010; Morrison, 2006).

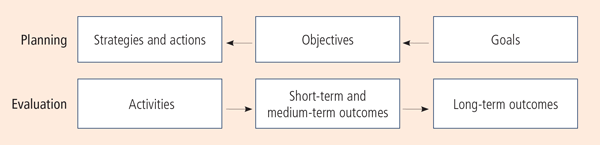

Box 2: Matching terms used in planning and evaluation

Many different terms and concepts tend to be used in the fields of program planning and evaluation. It can get confusing to figure out how they all work together. The Center for Disease Control (US) program planner resources describes the relationship between terms used in program planning and terms used in evaluation (see below diagram). Program plans work from abstract or conceptual goals to more tangible objectives, which are then translated into the strategies or actions needed to achieve them. Evaluation starts from the strategies or activities planned, with the program objectives indicating who will be the target audiences and short-term/medium-term outcomes. The goal of the program is likely to reflect the long-term outcomes that would ideally be reflected in the evaluation.

Program logic

A program logic model sets out the resources and activities that comprise the program, and the changes that are expected to result from them. It visually represents the relationships between the program inputs, goals and activities, its operational and organisational resources, the techniques and practices, and the expected outputs and effects.5 Other terms that are commonly used for models that depict a similar causal pathway for programs are theory of change, program theory and logic models.

Program logic is a critical element in an evaluation because it sets out a graphic and easily understandable relationship between program activities and the intended outcomes of the program. Two words are important to consider in this definition:

- Relationship - a logical link should be seen between each stage of the program logic model. There should be a clear relationship between the activities that are being undertaken, and the outcomes that are proposed.

- Intended - the program logic model serves as a roadmap for the program. The model shows why the activities, if implemented as intended, should effectively reach the desired outcomes.6

By referring to the model on a regular basis, you will have a deeper understanding about where things can go or have gone right or wrong, and the model can be adapted accordingly. It is also a good tool for educating and informing staff and other stakeholders about the program and the evaluation. Each part of your logic model needs to have enough detail so that it is apparent from examining the model what you need to do or to measure in order to demonstrate whether the intended changes occur.

Tip: Logic models

Logic models can be easier to develop when you start from the outcomes end and work your way backwards (McCawley, n. d.).

There are, however, some points to remember when creating a program logic model:

- programs can be complex and changeable;

- some unintended consequences of programs may not be accounted for in a model; and

- some interpersonal factors (resistance to the evaluation, lack of cooperation among different parts of the agency) that might affect the implementation of a program evaluation may not be incorporated (Shackman, 2008).

Some program models include consideration of external factors that may impact on the program, such as the interpersonal factors outlined above, and assumptions that have been made when the model was created, such as adequate funding being available. As such, it is important to regularly revisit the program logic and revise and update it as needed.

Program logic resources

- The logic model for program planning and evaluation (PDF 85.4 KB) (University of Idaho, US) - This brief article provides a good introduction to developing program logic models.

- Introduction to Program Evaluation for Public Health Programs: A Self Study Guide (PDF 2.8 MB) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US) - This comprehensive guide covers the process of describing the program and developing a logic model, starting simply and building to more complicated forms.

- Program Development and Evaluation: Logic Model (University of Wisconsin, US) - An online, self-study module on logic models is provided on the site, along with templates and examples of logic models.

Evaluation designs

The design of your evaluation will be determined to a large degree by the question(s) you are seeking to answer and the resources - time, money, staff, skills, etc. - that are available to you. The stronger the design, the more confidence you can have in the findings.7 There are many methods to choose from that differ in their degree of scientific rigour; in particular, how they affect your capacity to say that any effects can be attributed to the program or intervention. Ideally, however, an evaluation will comprise pre- and post-test data collection and at least one comparison group - or even better, a control group (Lamont, 2009).

Pre- and post-test design

In this design, factors relating to the objectives of the program are assessed prior to the program and then at the end of the program to determine whether there have been any changes. For example, a program aimed at improving a specific aspect of couple relationships, such as communication styles, would measure that behaviour in the couples before they enter the program. The same measures are taken again, in the same way, at the end of the program. The difference between the two measures will indicate whether and how much change has occurred, and in which direction.

What's good about pre- and post-test designs?

- The pre-test provides a baseline measure of the behaviour or attitude or skill level of interest, which helps to assess the severity of the problem and can guide selection of the appropriate intervention.

- They can be fairly simple to implement.

- They can demonstrate that when a program is provided to improve something, such as a client's parenting skills, that it actually does improve.

What's not so good about pre- and post-test designs?

- There may be other reasons why any observed change in behaviour occurred. You can't say definitely that the changes are due to your program.

- You can't demonstrate that if the program had not been provided, then no change would have occurred.*

* For a clear explanation of the logic underlying this argument, see Trochim (2006).

The way to overcome these limitations is by including other groups in your evaluation, as outlined next.

Comparison/control groups design

Comparison groups

Evaluating a single group of participants can demonstrate whether a change has occurred, but does not provide evidence that the program itself was responsible for that change. Collecting the same pre- and post-test data from a comparison group of people who do not participate in the program (or who are participating in a brief version of the program, or another, similar program) can strengthen your evaluation. A program may have a positive impact, for example, on self-esteem, but without the inclusion of a comparison group, it is unclear whether the program participants would have improved over time anyway, without experiencing the program.

What's good about comparison groups?

- They allow for a greater measure of confidence in the program effects - if program participants' self-esteem improves significantly, but that of the comparison group does not, then the program can be considered to have a degree of effectiveness in improving self-esteem (Lamont, 2009).

- They can be relatively easy to implement.

- Waiting lists can offer a ready-made comparison group that is similar in many respects to the participant group, and tend to be easily accessible within this sector.

What's not so good about comparison groups?

- A comparison group drawn from a waiting list might be quite similar to the group actually participating in the program, but they also might not be. The problem is that these pre-existing differences may be the reason for post-program differences between the groups, rather than the experience of your program itself. For example, the clients in your comparison group might be more highly educated, or experiencing less severe problems, or from a particular ethnic group, older, different family type than those who participate in your program.

- It may take longer to recruit enough participants for the two groups.

- Drawing a comparison group via your waiting list may cause some ethical concerns because their receipt of assistance via the program will be delayed. This may mean you need to find another way to create a comparison group.

- While on your waiting list to participate in the program, a comparison group member may read a self-help book, attend another course, or talk with someone who is already participating in your program (perhaps in your reception area). The behaviour or attitudes or knowledge of the people on the waiting list may change as a result of any of these things occurring and be reflected in differences between their pre- and post-test scores. Their problems may even resolve themselves through the passage of time or the progression of normal development.

- The amount of data to be collected and analysed doubles.

Control group(s)

The key problem with comparison groups is the possible lack of similarity between the groups on factors that you don't measure, but that are relevant to the things you do measure. For example, the levels of relationship distress among the participants in a "rocky relationships" group should be roughly equal to (or at least not significantly different from) those of the non-program group.

By randomly allocating clients to either participate or not participate in the intervention, you reduce the possibility of bias in the membership of the groups. This way, your "rocky relationships" intervention group won't contain a majority of couples who are only moderately distressed and your control group won't contain a large proportion of couples who are extremely distressed, or vice-versa.8

Random allocation of participants also means that clients won't have self-selected into each group. That is, couples who volunteer for a rocky relationships program might be the kind of couples who are highly motivated to apply what they learn in the program to their relationship. Their outcomes may be due more to their being highly motivated than to your program. With random allocation, the group in which a couple actually participates is under the control of the evaluator.

While establishing comparison groups on the basis of variables such as age, sex, education, relationship status, level of parenting confidence, number of problematic child behaviours etc., is not usually especially difficult, it is important to note that there are some dimensions on which participants might differ that will remain unknown to you, the evaluator. With a control group design, you collect the same data from the control group in the same way, at about the same time, as you collect from the group actually attending the program. This method is known as a randomised controlled trial (RCT) or experimental design.9

Box 3: Comparisons to population data

It may also be worth considering whether there are population-level data available that can provide you with comparative information about the characteristics of your clients or program participants. These might include: indicators of the level of social disadvantage in the areas from which participants are drawn, the prevalence of particular cultural or religious groups, or the incidence of some medical conditions. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) have a range of publications and products available to provide this information, and you may also be able to purchase data about specific locations or regions (see the ABS website). The ABS also provides the facility to explore and compare regional profiles .

Further sources of information about regional demographic data can be found on the CFCA Facts and Figures: Families and relationships web page.

What's good about using control groups?

- They are regarded as a rigorous evaluation method because random allocation ensures that all potential participants have an equal chance of being in the control or program groups, thus reducing the chance of the groups being different before the program starts.

- If the groups differ significantly at the end of the program period, you can be fairly confident that the program brought about the differences.

What's not so good about using control groups?

- RCTs are often difficult to implement in a service environment and can be expensive in terms of time, money and other resources.

- As with comparison groups, participants' behaviour or attitudes or knowledge may change as a result of other things - such as time passing, normal development, or reading a self-help book - and not their participation on the program.

- There is considerable debate as to their application in certain contexts, particularly where ethical concerns arise relating to withholding access to a potentially life-saving intervention. For example, RCTs may not be appropriate to evaluate a pilot program that is intended purely to see what, if any, effect a new program has on participants, or for assessing the effects of prevention of HIV/AIDS through safe-sex practices. It is also unethical to randomly assign a person to receive an intervention that may put them at risk of harm or distress. (See Tomison, 2000; Bickman & Reich, 2009, for more comprehensive discussions of RCTs. See also National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, & Australian Vice-Chancellor's Committee, 2007.)

Further improving your evaluation design: Follow-up testing

The methods outlined above can help you demonstrate whether your program contributed to changes for its participants for the duration of the program. However, it is also useful to know whether the benefits to participants are maintained over time. For example:

- Are they still using constructive conflict techniques?

- Are they still applying the coping strategies they were taught?

- Is their relationship with their child the same or better than it was at the end of the program?

Such follow-up testing can provide powerful support for your program or indicate that an adaptation to the delivery model (such as the addition of monthly or yearly "tune-up" sessions) might be warranted.

The same measures taken prior to and at the end of the program can be taken again some time after the conclusion of the program, perhaps a month or 6 months later. Follow-up measures might continue at regular intervals for a number of years, depending on the resources you have for this activity.

What's good about follow-up testing?

- It can identify which benefits of a program last, and how long.

- It can pinpoint when the application of a skill or strategy begins to wane, and so identify if/when "booster" sessions might be warranted.

- Evidence of lasting effects can contribute to future funding requests and obtaining support from stakeholders.

What's not so good about follow-up testing?

- It can be costly and challenging in terms of the resources needed to locate, track and contact past participants.

- Systems, resources and infrastructure need to be in place at the beginning of the evaluation process.

- Permission to be re-contacted needs to be obtained from participants before they actually attend the program.

Data collection and analysis

When you have decided on the design of your evaluation, you need to consider the type of data to be gathered and the method of data collection. The foundations on which these decisions rest are the program objectives and the program logic.

Breadth and representativeness of data collection

To further strengthen the evaluation, data should be collected from as many participants as possible within the time frame available. For example, you might gather data from participants in six consecutive programs, or from all participants in a given program over the period of a year, or from participants in different locations. In addition, the sample should be representative of the population to which you want to extend the findings; that is, they should be of similar ages or cultural backgrounds, education, income, and/or other factors that are relevant to the program being evaluated.

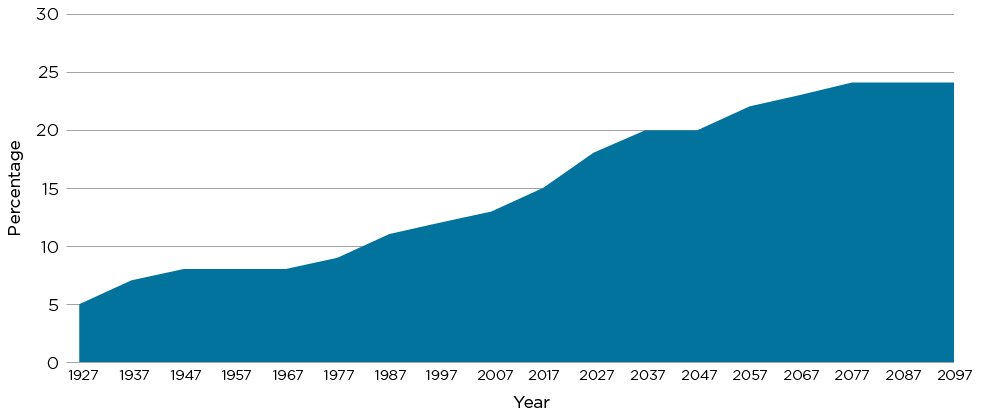

Figure 1 shows how combining evaluation design with broad, representative samples produces increasing effectiveness and strength of design.

Figure 1: Hierarchy of evaluation designs and data collection methods

Common data collection methods

It is important that the method of data collection is appropriate to the type of evaluation. For example, surveys and questionnaires may be relatively easy and efficient to conduct. If, however, your objective relates to, for example, improving parent-child interaction or changing couple conflict behaviour, then observational techniques may be more appropriate. This is because observation does not rely so much on participants' self-reports, which are vulnerable to people's need to present themselves in a good light. Observational techniques can, however, be extremely resource-intensive and are not often seen outside of university research laboratories. Since they involve direct communication with participants, interviews may be a better way of learning about clients' experiences, for example, of post-natal depression or the counselling they receive. Three common data collection methods - surveys or questionnaires; interviews; and focus groups - are further described below.

Surveys and questionnaires10

Surveys can allow you to collect a lot of information in a relatively short period, but unless you are using an established instrument,11 they require a great deal of planning and preparation, review and revision.

Tip: Using questionnaires with culturally and linguistically diverse groups

If you use an existing instrument, it is useful to check that participants who are likely to be attending your program understand the items. Cultural and language differences may lead to ambiguity and confusion. Testing of the items by people from various cultural groups can avert the loss of data (because the items are simply ignored) or avoid the collection of data that is inaccurate or misleading (because the questions are misunderstood).

As well as developing a new set of questions or adapting an existing instrument, you will probably also need to create:

- a cover letter or information sheet explaining the survey and why you are doing it;

- instructions on how to complete the survey;

- informed consent documents for respondents to sign;12 and

- procedures by which you can contact respondents for follow-up.

It pays to allocate sufficient time and resources for the development and testing of the items and the associated documents, as well as to the structure and layout, and procedures for identifying and following-up non-responders. Issues to be considered include:

- the number and types of questions ("closed", "open-ended" and "filter"; see Box 4);

- the response scales for the questions (e.g., will participants circle the words "yes" or "no", or will they tick a box or circle a number; will the numbers range from 1 to 5, or 0 to 10; will you allow a middle value to allow for "undecided" or neutral responses);

- the "anchors" for the questions (e.g., "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree"; "not at all like me" to "very much like me"; "never" to "always");

- whether it is completed by respondents online, by mail, over the telephone, at home, or on arrival at the program; and

- how the data will be stored, analysed and reported.

These all need to be settled, tested (on colleagues, staff, volunteers, etc.) and revised if necessary before beginning the actual data collection. There is no better way to ensure the questions are easily understood, are taken to mean what you intend them to mean, and can be easily answered by the target respondents than by actually asking real people to complete draft versions. This also adds to the engagement of staff in the evaluation.

Box 4: Types of survey questions

Closed questions

1. Are you married? Yes No

2. What is your professional status? (Please tick as many boxes as apply)

- Psychologist

- Counsellor

- Social Worker

- Mediator

- Other

- Please specify

3. How would you rate the professionalism of the program facilitator?

| Very high | High | Moderate | Fair | Poor* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Open-ended questions

1. Which section of the training program did you find the most helpful?

Filter questions

Filter questions allow respondents to be directed only to those questions that are relevant to them. For example:

1. Do you have children? Yes No

If you answered "No", please go to question 3.

2. How many children do you have? (please insert the number)

3. Would you like to have (more) children? Yes No

* "Very high", "high", "moderate", etc. are the "anchors" for the item response.

Interviews

Questionnaires are generally highly structured, pre-planned, and designed to gather quantitative (numerical) data. Interviews tend to be less structured, spontaneous (in that questions may not necessarily be asked in a set order, or new questions may be prompted as the interview unfolds), and usually gather qualitative information (Alston & Bowles, 2003). Semi-structured interviews focus on a set of questions and prompts that allow the interviewer some flexibility in drawing out, responding to and expanding on the information from a participant. The interviewee's responses may be written down by the interviewer as the conversation progresses or recorded electronically. The recording may later be transcribed (although this can be costly if done by a professional transcription service). In-depth interviews may have little formal structure beyond a set of topics to be covered and an expectation on the part of the interviewer as to how the conversation might progress.

Interviewing people from Indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse groups

Interviews with Indigenous people or those from different cultural backgrounds may require particular skills and expertise. Indigenous agencies and local organisations, such as Migrant Resource Centres, can be sources of information and support to practitioners working with Indigenous clients and those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. For starting points, go to:

- Service provision - Culturally and linguistically diverse families and children

- Service provision - Indigenous families and children <https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/publications-articles/number-23-indigenous-families-and-children-coordination-and-provision-of-services?HTML>

Focus groups

A form of group interview, focus groups allow for information to be collected from several people at once in a much shorter time frame than if you conducted each interview separately. Thus, they can be a good way, when time and resources are short, to obtain both wide-ranging and in-depth information about a program from participants, managers and other stakeholders.

Interaction between participants can lead to high-quality information, but group pressure and dynamics may also lead to conformity, or to some participants being less engaged in the dialogue. The facilitator needs to ensure all members of the group have the opportunity to contribute, that all views are respected, and that the discussion remains on track.

Analysis of notes or transcripts can require a great deal of time and, as with interpretation of other qualitative data, may require that more than one person be involved in the identification and analysis of themes and issues (Stufflebeam & Shinkfield, 2007; Weiss, 1998).

To some extent, the type of data you collect will be determined by the specific instrument used to measure the variables related to the program objectives. Established scales, inventories or checklists have standard formats to be followed, but you may want to collect other information at the same time - demographic information, experiences and/or expectations of the service, attitudes or beliefs about issues related to the focus of the program, and so on.

Slightly different versions of the instrument may be required, depending on whether it will be completed by a program participant, a facilitator, counsellor, parent or a teacher. All the information to be collected needs to be collated into a single document and attention paid to how it looks, how it reads, and how easy it is for respondents to complete.

Data collection methods resources

- Alston, M., & Bowles, W. (2003). Research for social workers (2nd Ed.). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd Ed.). California: Sage Publications.

- Liamputtong, P., & Ezzy, D. (2009). Qualitative research methods (3rd Ed.). South Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford University Press. Chapter 3: In-depth interviewing, and Chapter 4: Focus groups.

- Trochim, W. (2006). The Research Methods Knowledge Base. Ithaca, NY: Web Center for Social Research Methods. Survey Research section.

Analysis of data

The method you use to collect your data - that is, the type of questions you ask and how participants indicate their responses - determines the type of data you will obtain, which will then determine the techniques that can be used to analyse that data. This in turn influences what you can say about whether and how your program affected participants. Two types of data can be collected: quantitative and qualitative.

Quantitative data

Quantitative data are numerical and are typically collected through methods such as surveys, questionnaires or other instruments that use numerical response scales. As a general rule, collecting data via numerical scales is preferred because numerical data can be analysed by a wide range of descriptive and inferential statistical techniques (see Box 5). Descriptive statistics include counts (e.g., number of "yes" and "no" responses), percentages and averages, while inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant relationships between the variables measured (Government Social Research Service, 2009).

Box 5: What are descriptive and inferential statistics?

When the quantitative data collection for your evaluation is complete there will a great deal of data arranged in rows and columns in a dataset. It is impossible to make much sense of these numbers just by looking at them, so statistical techniques are used to derive meaning from them.

Descriptive statistics summarise, organise and simplify the data so that its basic features become clear and it is more easily managed and presented. Using descriptive statistics, a great deal of data can be described by a single statistic; for example, the mean (or average) of scores on a parenting confidence scale of 100 parents of adolescent boys.

Inferential statistics serve a number of purposes. They tell you whether what you found (e.g., improvements in parenting confidence) in your sample (e.g., adolescent boys' parents who are participants in your program) is likely to occur in the general population from which your sample came (e.g., all parents of adolescent boys). They are also used to decide whether any changes you found (e.g., improved parental confidence) could have happened by chance or are likely to have resulted from their participation in your program. You can also find out whether two factors - such as parental confidence and number of social supports available to parents - are related to each other and how, and how strong that relationship is.

Source: Trochim, (2006)

The data most likely to be collected in a program evaluation are those that represent responses that signify a rank (for example: 1st, 2nd, to 10th; or 1 = high, 2 = middle, 3 = low), or that have an underlying order (for example: 1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = disagree, 5 = strongly disagree). You may also collect data that signify a rating on or perception of a variable such as a feeling (e.g., anxiety, enjoyment, fear, love, self-worth), a skill (e.g., parenting competence), or a behaviour (e.g., severity of tantrums) on a scale of, say, 1 to 5 or 0 to 10. The value of collecting data in this way is that the numbers can be manipulated statistically and so lend themselves to inferential statistical techniques that allow you to assess whether the changes in participants can be attributed to chance.

However, quantitative data are not always able to convey the complexities of participants' experiences or points of view, so qualitative data - written or verbal responses - may be preferred.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data typically comprise written or verbal responses collected via techniques such as interviews, focus groups, documents, and case reports, but may also be derived from other media, such as photography.13 Qualitative data can reveal aspects of the participants' experiences of the program beyond the more narrowly focused survey or questionnaire items. They can reveal a great deal about the complexity of participants' lives and the diversity of their views and experiences. They can also be used to complement or challenge findings from quantitative data, and provide insights into the subtleties of the program that may not be captured through quantitative methods (Stufflebeam & Shinkfield, 2007).

Analysis of qualitative data can allow data collection to be responsive to emergent or divergent themes. For example, if 3 or 4 participants mention a particular issue or experience spontaneously, the interviewer can incorporate a question about that experience into the interview schedule with subsequent participants.

This does not mean that analyses of qualitative data do not follow established procedures and do not require attention to rigour. A basic analysis of qualitative data might be primarily concerned with identifying key themes, but the process can also be a great deal more involved and require the use of specially designed computer packages. It can also be time-intensive, requiring time for reflection and interpretation.

Qualitative methods and analysis resources

- Ezzy, D. (2002). Qualitative analysis: Practice and innovation. NSW: Allen and Unwin. Chapter 4.

- Liamputtong, P., & Ezzy, D. (2009). Qualitative research methods (3rd Ed.). South Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford University Press.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Stufflebeam, D. L., & Shinkfield, A. J. (2007). Evaluation theory, models, and applications. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Trochim, W. (2006). The Research Methods Knowledge Base. Ithaca, NY: Web Center for Social Research Methods. Qualitative measures section.

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods

A single variable (such as relationship satisfaction, sense of mastery, parenting confidence) may be measured by quantitative or qualitative means. A combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection is called a mixed methods approach. For example, a quantitative survey or questionnaire may include one or more open-ended items that ask for a verbal or written (qualitative) response from a participant. Or a study of couple relationships might include observations of couples (qualitative) as well as partners' self-report responses to a relationship questionnaire (quantitative). Qualitative data can be analysed in several ways to identify key issues or themes, and are useful because they can also be coded into numerical data and analysed by inferential statistical techniques.

Gathering different types of evidence by collecting both qualitative and quantitative data from various sources and combining different designs can improve the depth, scope and validity of the findings of the evaluation.

The type of data collected and the way in which it will be analysed and reported are integral to the successful implementation of an evaluation plan - they must be considered in the early stages of its development along with the other "who", "what", "how" etc. questions. While some parts of the evaluation will require the collection of fairly simple data, when you are seeking to influence complex attitudes, behaviours, circumstances or skills and knowledge a considerable amount of thought and planning will be required to ensure the data are able to adequately answer the evaluation questions.

References

- Alston, M. & Bowles, W. (2003). Research for social workers (2nd Ed.). Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Bickman, L., & Reich, S. M. (2009). Randomised controlled trials: A gold standard with feet of clay? In S. I. Donaldson, C. A. Christie, & M. M. Mark (Eds.), What counts as credible evidence in applied research and evaluation practice? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from <www.cdc.gov/eval/guide>.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases. (2006). Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: Evaluating appropriate antibiotic use programs. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from <www.cdc.gov/getsmart/program-planner/Introduction.html>

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Writing SMART objectives (PDF 213 KB) (Evaluation Briefs No. 3b). Retrieved from <www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/evaluation/pdf/brief3b.pdf>.

- Ezzy, D. (2002). Qualitative analysis: Practice and innovation. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Gottman, J. (1994). Why marriages succeed or fail. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Government Social Research Service. (2009). The Magenta Book: Guidance notes for policy evaluation and analysis. London: Government Social Research Service. Retrieved from <www.civilservice.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/the_complete_magenta_book_2007_edition2.pdf>.

- Haughey, D. (2010). SMART goals. UK: Project SMART. Retrieved from <www.projectsmart.co.uk/smart-goals.html>.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lamont, A. (2009). Evaluating child abuse and neglect intervention programs (NCPC Resource Sheet). Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/sheets/rs5/rs5.html>.

- Liamputtong, P., & Ezzy, D. (2009). Qualitative research methods (3rd Ed.). South Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford University Press.

- McCawley, P. F. (n. d.). The logic model for program planning and evaluation (PDF 85.4 KB). Moscow, ID: University of Idaho Extension. Retrieved from <www.uiweb.uidaho.edu/extension/LogicModel.pdf>.

- Morrison, M. (2006). How to write SMART objectives and SMARTer objectives. Twickenham, Middlesex: Rapid Business Improvement. Retrieved from <www.rapidbi.com/created/WriteSMARTobjectives.html>.

- National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, & Australian Vice-Chancellors' Committee. (2007). National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Canberra: NHMRC.

- Owen, J., & Rogers, P. (1999). Program evaluation: Forms and approaches (2nd Ed.). Sydney, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Shackman, G. (2008). What is program evaluation? A beginner's guide (PDF 217 KB). Albany, NY: Global Social Change Research Project. Retrieved from <gsociology.icaap.org/methods/evaluationbeginnersguide.pdf>.

- Stufflebeam, D. L., & Shinkfield, A. J. (2007). Evaluation theory, models, and applications. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Tomison, A. (2000). Evaluating child abuse protection programs (Issues in Child Abuse Prevention No. 12). Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Retrieved from <www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues12/issues12.html>.

- Trochim, W. M. K. (2006). Research Methods Knowledge Base. Ithaca, NY: Web Center for Social Research Methods. Retrieved from <www.socialresearchmethods.net>.

- United Nations Evaluation Group. (2005). Standards for evaluation in the UN system. New York: UNEG. Retrieved from <www.uneval.org/papersandpubs/documentdetail.jsp?doc_id=22>.

- Weiss, C. H. (1998). Evaluation (2nd Ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Footnotes

1. Planning for Evaluation II: Getting into Detail drills a little further into the evaluation process to prompt thinking and planning for the multitude of small, yet important, issues and questions that, if not addressed, can quickly derail an evaluation.

2. It's important to keep in mind the differences between program objectives and evaluation objectives. Evaluation objectives flow from the bigger picture-the purpose and scope of the evaluation-whereas a program objective refers specifically to what the program itself is intended to achieve. Evaluation objectives might refer to program implementation, identification of the strengths and weaknesses of a program, and/or recommendations for planning and management of resources (United Nations Evaluation Group, 2005).

3. See Planning for Evaluation II: Getting into Detail for sources of tools and instruments.

4. Organisational goals such as these can be more correctly referred to as outputs-products of the program activities (Owen & Rogers, 1999). For example, the value of an outreach program may be measured by the number of contacts made by the particular type of potential client in a defined period, while a community information campaign might be assessed by the number of hits on a website.

5. The outputs and effects can be immediate, short-term, medium-term or long-term. Because of limited resources, your evaluation may only be able to assess, for example, the immediate or short-term effects of your program. If that is the case, make it clear in your evaluation report that you are only assessing those particular effects, and why.

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases (2006), see "Step 2 - Describe the Program"

7. See Evidence-Based Practice and Service-Based Evaluation for further discussion of this issue.

8. Of course, this could happen by chance but, statistically, it is extremely unlikely.

9. RCTs are also discussed in Evidence-Based Practice and Service-Based Evaluation.

10. In doing your evaluation, you might be assessing a range of things, from, for example, participants' mental health (using an established inventory of symptoms), to their current relationship health (using a 100-item scale), to their age and income and the number of children they have. The instruments used to measure each of these will have a particular format or structure and require different kinds of responses from participants. When the instruments are administered to participants, they are likely to be compiled into a single document, which can be referred to as a questionnaire. In this resource, the term "questionnaire" can be taken to include the compilation of various measures to which participants respond.

11. See Planning for Evaluation II: Getting into Detail for more on this subject.

12. For further information about informed consent, see Evidence-Based Practice and Service-Based Evaluation.

13 An example of the use of photography is Photovoice, a method used often in community development and public health programs, particularly with marginalised groups. See an example of the use of Photovoice and links to resource.

This paper was first developed and written by Robyn Parker, and published in the Issues Paper series for the Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse (now part of CFCA Information Exchange). This paper has been updated by Elly Robinson, Manager of the Child Family Community Australia information exchange at the Australian Institute of Family Studies.