Parental Leave Pay and Dad and Partner Pay: Patterns of use

Analysis using the Person Level Integrated Dataset (PLIDA)

December 2023

Download Research report

Overview

This research report explores how the Australian Government's Parental Leave Pay (PLP) and Dad and Partner Pay (DAPP) were used by families up to December 2022. As well as providing an overview of recipient numbers, it provides insights on which families were using PLP and DAPP and how they were using it, highlighting which families are most likely to be using these payments straight after the birth. For example, young mothers and mothers with lower levels of educational attainment are most likely to be using PLP early, suggesting a lack of access to employer-funded leave, and affirming the value of PLP in supporting these mothers' connection to employment. This research report is the first output from the project 'Statistical profile of use of Paid Parental Leave and Dad and Partner Pay', using the Person Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA), previously named MADIP (Multi Agency Data Integration Project). The project explores the use of PLP and DAPP making use of linked data in PLIDA. The primary data source is administrative data from the Department of Social Services (DSS) resource 'Data Over Multiple Individual Occurrences' (DOMINO), with DOMINO tables stored in PLIDA. These data have been linked to data from the ABS Census of Population and Housing (Census) and other administrative data. The analysis of linked Census data shows that at a point in time (on Census night) about one in five mothers of a child under one year of age were using PLP, with there being distinct patterns in use in the months following the birth. For DAPP recipients, this number as a percentage of new fathers is much lower, at about one per cent. The report also includes analysis of how PLP and DAPP are used, about timing of use, and how PLP and DAPP are sequenced in couples where both are taken. Finally, some analysis shows the extent of other kinds of financial support received by families in this period after the birth of a child, focusing on DSS-administered government income support payments, benefits and allowances.

1 Introduction

This research report is the first output from the project 'Statistical profile of use of Paid Parental Leave and Dad and Partner Pay', using the Person Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA), previously named MADIP (Multi Agency Data Integration Project). The project explores the use of the Australian Government's Parental Leave Pay (PLP) and Dad and Partner Pay (DAPP), making use of linked data in PLIDA.

This is the first piece of comprehensive research that documents the use of PLP and DAPP since the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) 2015 report of the review of the Paid Parental Leave Scheme and the Paid Parental Leave scheme final evaluation report (Martin, Baird, Brady et al., 2015). The analysis here extends and updates the administrative data analysis that was presented in that report. While regular DSS reporting provides some key demographic information on PLP and DAPP recipients,1 there is no information that delves into the ways in which these payments are used, and how use varies across different families. The lack of current information on PLP/DAPP was recently noted by Baird (2021), whose article highlighted the value of data in the ongoing consideration of this policy area.

With changes to PLP and DAPP having started in 2023 and expected to roll out over coming years, this report provides some contextual information on how these payments are used under the scheme to date. For more information on these reforms see Boosting Parental Leave to Enhance Economic Security, Support and Flexibility for Australia's Families (dss.gov.au). A summary is provided in section 2.2 below.

The report shows how PLP and DAPP has been used up to December 2022, under the pre-Reform scheme, and how it varies across different kinds of families. The focus is on three broad research questions:

- What are the characteristics of PLP and DAPP recipients, and have these characteristics changed since the schemes' introductions?

- How are families using PLP and DAPP - what can be said about the timing of use and how it varies in different families?

- To what extent is PLP (and DAPP) used across all families with children under one year of age, and if not PLP, what other financial supports are they accessing?

The primary data source is administrative data from the DSS resource 'Data Over Multiple Individual Occurrences' (DOMINO), with DOMINO tables stored in PLIDA. In PLIDA, these data can be linked to Census and other administrative data. Additional research uses the Census data, and using Census data linked with DOMINO, to report on families with a child under one year of age, and their use of PLP, DAPP and some other DSS-administered government payments. A second report will extend this research, making more use of the linked Census-DOMINO data. More information about the data is provided in the Data section below.

This research does not explore the use of employer-funded parental leave, given information on this is not available in the PLIDA datasets. The availability of this leave is no doubt relevant to families' use of Government-funded PLP and DAPP, and links between parents' job characteristics and PLP use will be a focus of a second report. The background section below includes some contextual information about parental employment and leave.

1 Information about PLP and DAPP is available through DSS regular reporting on all payments and programs. This includes annual reports and quarterly statistics DSS Benefit and Payment Recipient Demographics - quarterly data - Dataset - data.gov.au

2 Background

2.1 Family composition

The focus of this report is on families with children under one year of age and includes some analysis of single and couple parent families, and reference to opposite-sex and same-sex couple families. By way of background, it is useful to note that the vast majority of children under one year of age live with both parents. Qu and Baxter showed that at the 2021 Census, 82% of children under one years old lived in an intact family (with both biological/adoptive parents), 8% lived in a stepfamily or blended family, and 10% lived with a single parent (see Qu & Baxter, 2023a). While the number of same-sex couple families is increasing (see Qu & Baxter, 2023a, using census data), the incidence among new parents is expected to be very low. In 2021, of all couple families only 1.4% were same-sex couples. Family composition of PPL and DAPP recipients will be explored in this report.

2.2 Parental employment and leave

Mothers and fathers and employment

Recent AIFS analysis of Census data shows continuing gendered patterns of employment among parents of young children, with fathers likely to continue in full-time employment when children are young, and mothers likely to reduce engagement in paid work. In 2021, for example, within couple families with a child under one year of age, in 24% both mother and father were employed and working more than zero hours, in 61% only the father was working more than zero hours, in 2% only the mother was working more than zero hours and in 13% neither parent was employed or at work.

While 'zero hours' includes mothers (or fathers) in casual employment who were without work in the reference period for the Census, it is very likely that for mothers with newborns, this category largely reflects mothers who are on leave from employment.

This analysis showed, for mothers with a child under one year of age, marked increases over recent decades in the percentage who were employed. The increase, though, was almost entirely explained by the growth in the percentage of employed mothers working zero hours. Between 1991 and 2021, the percentage employed mothers increased from 30% to 57%, and within that, the percentage employed but working zero hours increased from 5% to 32%.

Access to maternity leave or parental leave, that allows mothers to remain connected to employment while taking a break to care for newborns, is important in facilitating this ability to be employed but working zero hours. Access to paid leave is especially useful, which is an important contribution of Paid Parental Leave.

Workplace perspectives - overview

Paid Parental Leave and Dad and Partner Pay are both options for eligible parents, allowing them to extend leave conditions that may be offered by their employer. The availability of these payments is especially important for self-employed and casual workers, or other workers without leave entitlements. This report does not include workplace characteristics in its examination of PLP and DAPP use, but the availability of employer-provided parental leave (in part of the labour force) is discussed below, for some context.

For a broader perspective on the availability of leave in the public sector, the June 2023 Maternity Leave Act review report presents useful summaries.

Workplace perspectives - private sector

Employer-level data about parental leave provisions is reported by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), using data on non-public sector employers with more than 100 employees. In the WGEA Gender Equality Scorecard covering 2021-22, it was reported that 62% of employers offered paid primary carer's leave (either to both women and men or to women only), with this leave at least partially funded by the employer. While the proportion has increased slowly year on year, it has increased markedly over a longer time. For example, in 2013-14, 48% of employers offered paid primary carer's leave.

There is considerable variation across the labour market in the availability of paid parental leave. Small employers are less likely to offer paid primary carer's leave. For example, in 2021-22, among those employing less than 250 people, 44% offered no paid primary carer's leave. At the other end of the scale, 14% of those with 5,000 or more employees offered no paid primary carer's leave.

Similarly, there are marked differences by industry of employment, noting the scope is non-public sector employers with more than 100 employees. For example, in 2021-22:

- Access to paid primary carer's leave was most likely in industries of Education and Training (87%), Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services (87%), and Financial and Insurance Services (86%).

- Access to paid primary carer's leave was least likely in industries of Accommodation and Food Services (36%), Retail Trade (36%), Administrative and Support Services (35%) and Public Administration and Safety (26%).

The majority (92%) of employers make the primary carer's leave accessible to men and women with only 8% of employers providing primary carer's leave to women only in 2021-22. There is, however, a very gendered pattern to the use of primary carer's leave, with 87% of primary carer's leave taken by women in 2021-22. Among non-managers it is 88% and managers 76%. WGEA reports that there has been some increase in the proportion of men taking the primary carer's leave.

Some employers are aiming to improve the gender balance in parental leave use, and to make more equitable access to leave for varied family circumstances. They are removing the reference to 'primary' or 'secondary' carer status, or gender, and offering equal amounts of leave to all new parents or caregivers. Of employers offering paid parental leave in 2021-22, 24% had a gender-neutral approach, without a primary/secondary carer distinction.

Within the data held by WGEA, most employers (84% in 2021-22) fully paid for the employee's salary for the period of paid parental leave. The balance includes 10% that paid the gap between the salary and the pay from the government's Paid Parental Leave scheme, and 6% that paid the leave amount in a lump sum.

At 2020-21 the average length of primary carer's leave was 11.1 weeks. Underlying these averages, 14% of employers offered 1-6 weeks, 24% offered 7-12 weeks, 16% offered 13-17 weeks, and 7% offered 18 weeks or more. In contrast, the average length of secondary carer's leave was 2.3 weeks in 2020-21.

Evaluation findings about PLP and job retention

The evaluation of the Paid Parental Leave scheme considered a number of outcomes of the scheme, one of them being how it had impacted mothers' return to work timing and job retention. Their analysis showed that the introduction of PLP was associated with a lesser proportion of mothers being back at work in the early months after a birth, but that by 6 months after the birth, the introduction of PLP saw a small rise in the proportion of mothers at work. That is, PLP provided an opportunity for mothers to be at home for longer, while remaining connected to employment. This impact was most marked for low-income mothers and mothers who were self-employed or in casual jobs before the birth. These findings were consistent with expectations and the objects of the policy. Impacts on employment were less apparent for high income women, which was attributed to the wage replacement of PLP (at minimum wage) being low relative to usual income for these women, and these women also being more likely to have access to paid leave through their employer.

Given these findings, it is expected that use of PLP in the early months after the birth will be most apparent among low-income mothers and mothers without access to employer-provided parental leave.

Evaluation findings about DAPP

DAPP was evaluated as part of the evaluation of the Paid Parental scheme (see Martin et al., 2015). Findings suggested that the introduction of DAPP altered how fathers took leave after the birth, with the potential to access DAPP while on unpaid leave meaning some fathers chose this option rather than using their paid annual leave after the birth. The introduction of DAPP did not see an increase in the proportion of fathers taking leave after the birth, but slightly increased the average length of leave taken. In summarising the findings for the evaluation of DAPP, Martin et al. (2015) noted that the categories of fathers that benefited substantially from DAPP were 'Fathers who previously had no access to paid leave following a birth, particularly employees on casual contracts, contractors and sole traders' and 'Fathers who had exhausted other paid leave (especially annual leave) and had high family support demands that could not be met in other ways'.

2.3 Australian policy content - PLP and DAPP

Parental Leave Pay

The Australian Government's Paid Parental Leave scheme commenced in 2011, being available to eligible parents with birth or adoption dates from 1 January 2011. Parental Leave Pay(PLP) is a payment under the Paid Parental Leave Act 2010. PLP is not a leave entitlement, although it sits alongside the unpaid parental leave provisions under the Fair Work Act 2009. More detailed information about the scheme and other provisions can be found in Baird, Baxter and Hamilton (2023).

The scheme (to June 2023) provides up to 18 weeks of pay to eligible working parents at the rate of the national minimum wage. At March 2023 the rate of payment was $812.45 per week (before tax). PLP recipients may negotiate with their employer to top up this amount to bring their income back to the usual amount without this impacting their PLP payment.

Typically, the recipient is the mother. The eligibility conditions require recipients to be the primary carer of a newborn or adopted child, and one of the following:

- the birth mother of a newborn child

- the initial primary carer of an adopted child placed in your care by an authorised party for the purpose of adoption

- another person caring for a child under exceptional circumstances

- someone to whom the previous primary carer has transferred some or all of their Parental Leave Pay.

As indicated in the above, all or some of the PLP can be transferred from the mother to another primary carer, such as the child's father or the PLP recipient's partner. This second recipient would also need to meet eligibility criteria.2

Eligibility to PLP is based on an income test and work test (see Box 1 below), as well as being subject to residency requirements. (Note that this report reflects the Paid Parental Leave scheme, including eligibility rules that applied before the changes on 1 July 2023).

Box 1: Income and work test

The income test is based on the applicant's individual income in the year prior to the birth or adoption. It uses adjusted taxable income. If the 2021-22 financial year income was assessed, to be eligible the adjusted taxable income had to be $156,647 or less.3 If the 2020-2021 financial year income was assessed the limit was $151,350, for 2019-20 and earlier years the limit was $150,000.

The work test requires recipients to have worked at least 10 of the 13 months before the birth or adoption, involving at least 330 hours of paid work, without a break in employment of more than 12 weeks. Paid leave counted as work and from 1 March 2014, periods of PLP and DAPP within the 13-month window counted toward the work test. As parents' work was often disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic, periods on JobKeeper Payment or the COVID-19 Disaster Payment also counted toward the work test.

PLP can be taken at any time (in one block) up until the child's first birthday, although with the introduction of Flexible Paid Parental Leave in 2020 (described below), a portion of it may be used flexibly and taken any time up to the child's second birthday.4 PLP can be taken while also receiving leave entitlements (including paid leave) from the recipients' employer. New parents may instead choose to use the PLP once the paid leave from their employment concludes. As PLP is a payment, rather than guaranteed leave, the timing of leave-taking and return to work needs to be negotiated with employers.

Dad and Partner Pay

Dad and Partner Pay (DAPP) was introduced in 2013, providing two weeks at the national minimum wage rate for eligible fathers and partners. This applied to those who cared for a child born or adopted from 1 January 2013. As for PLP, the DAPP rate was $812.45 per week (before tax) at March 2023. DAPP recipients may negotiate with their employer to top up this amount to bring their income back to the usual amount without this impacting their DAPP payment.

DAPP is to be taken in the year after the child's birth and can only be taken while on unpaid leave. DAPP cannot be transferred to the mother.

Eligibility is subject to the same income test and work test that applies to PLP (see Box 1). Eligibility is also subject to residence rules and requires that fathers care for the child on each day of the DAPP period.

Flexible Paid Parental Leave

From July 2020, families have had the option of taking the first 12 weeks of PPL in a continuous block, then using the final six weeks as Flexible Paid Parental Leave (FPPL), including using it to return to work part-time by using the leave on a part-time basis, or sharing the leave with someone else. The first 12 weeks needed to be taken before the child's first birthday, and the remaining 6 weeks could be taken any time after using up the first 12 weeks until the child's second birthday.

Changes 2023 and beyond

Changes to the Paid Parental Leave scheme were introduced from 1 July 2023 with more changes expected to be rolled out in subsequent years. The key changes in July 2023 are described below:

- The removal of DAPP as a separate payment, with PLP now designed for sharing between parents. PLP was extended to 20 weeks to include the 2 weeks previously covered by DAPP. This is equivalent to a total of 100 days of PLP.

- Within couples, each parent can use at most 90 of the 100 days, with the remaining 10 days reserved to share with the other parent if they are eligible. That is, if the birth mother is eligible for PLP, she can choose to share the 100 days of PLP, but if she has a partner and she elects to use it all herself she cannot use more than 90 days.

- Single parents can access the full 100 days if they choose not to share the PLP with another parent.

- Each parent can take up to 10 days of the PLP at the same time.

- Partners can only access a share of PLP if they themselves are eligible and the birth parent meets the work test. That is, fathers cannot access a share of PLP if mothers have not met the work test for PLP.

- A family income test was introduced, so that if parents are ineligible for PLP because their income is above the personal income cutoff ($168,865 in 2022-23 and $156,647 in 2021-22) they can access it if their family income (e.g., birth parent income plus partner income) is less than a higher cutoff ($350,000). This family income test can also be applied if the claimant is a single parent.

- Parents can take PLP while on paid or unpaid leave from work. This was previously the case for PLP, but not for DAPP, for which fathers could not be on paid leave.

For more up-to-date and detailed eligibility information as well as specifics relating to adoptions, sharing care with people other than parents, and special circumstances refer to the Services Australia website.5

This report includes data up to December 2022, so does not cover the impacts of these changes. This research will provide context to these changes, with later analysis able to consider how the 2023 (and beyond) changes are accompanied by changes in use. The final section of the report includes a subsection that summarises how the findings presented here might be different under the new arrangements.

Alternative and supplementary payments

PLP and DAPP are intended to provide financial assistance to parents who are taking leave from employment to care for a newborn or a newly adopted child. They are therefore relevant to those in employment and, as noted previously, are subject to a work test and income test. There are alternative and supplementary payments and allowances available to families who do not meet these requirements. The availability of these financial supports has varied over the period covered in this report. Refer to the PLP and other DSS payments section for a summary and brief analysis of the coverage, focusing on DSS payments (that is, government payments, allowances and benefits administered by DSS).

2 A criticism of these eligibility conditions was that for the PLP to be transferred to someone else (say, the father), the mother had first to be eligible. So in cases where the father was the low income earner, he may have been precluded from accessing PLP if the mother's income exceeded the income threshold. The July 2023 changes introduced a family income test that assesses eligibility at a second stage for those failing on the individual income test.

3 The income test is based on 'adjusted taxable income'. This includes taxable income from sources like wages and salaries, business and investment. It also includes some pensions and benefits, although payments not included are Family Tax Benefit and Child Care Subsidy.

4 The focus of this report is on the first year after the birth, as the analysis shows that by the child's first birthday, only a small proportion of parents are using PLP.

5 See Who can get Parental Leave Pay for a child born or adopted from 1 July 2023 - Parental Leave Pay for a child born or adopted from 1 July 2023 - Services Australia

3 Data and method

3.1 Data

DOMINO data

This research is a PLIDA project, drawing on administrative data about PLP and DAPP, about the recipients of these payments and their characteristics. The administrative data about these payments comes from the DSS resource 'Data Over Multiple Individual Occurrences' (DOMINO), with DOMINO tables stored in PLIDA, and able to be linked to Census and other data. For this report the scope was limited to anyone starting PLP or DAPP before January 2023.6

For analysis from DOMINO, all recipients of PLP and DAPP since the commencement of each payment were in scope for this research. Characteristics of recipients, families and children were extracted and linked from different tables in DOMINO and compiled into one analytical dataset. From the DOMINO data, information was extracted on gender, age, whether Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, country of birth (presented here as whether Australian-born), relationship status (and gender of partner if applicable) and child month and year of birth.7 Some family variables were derived: the number of children born prior to the one for whom PLP or DAPP is being used, and whether the 'PLP/DAPP' child is one of a multiple birth, for example.8

Some information was accessed from other linked data.

- The 'combined location' data in PLIDA was used to identify which State they were located in and the remoteness at commencement of payment. This information was only current to June 2021, so was missing for many newer PLP/DAPP recipients.9

- The 'combined demographics' information in PLIDA was used for whether Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. This information was only current to June 2021, so was missing for many newer PLP/DAPP recipients. The DOMINO measure was used where this information was missing from the combined demographics data.

- Income data was derived from the ATO data, using the financial year total profit and loss amount variable. It was matched by individuals' identification variables to all recipients of PLP and DAPP. Data for the financial year before the PLP/DAPP commencement was matched for the purposes of analysis reported here.10

The file that was created from the above information contains all episodes of PLP and DAPP payments since the schemes' commencement. Each row largely reflects the total amount of PLP or DAPP used for one child, but in a small number of cases the PLP payment has been split across different recipients. The data are further manipulated to report couple-level and family-level data, all achieved by reformatting the data to different units of measurement. Some of the later child-level analysis present the data in more detail, looking at timing of access by exploring the data at a monthly level for each child.

- There were over 2.75 million records in the final analytical dataset, relating to all PLP and DAPP episodes.

- The child-level dataset contained about 2.1 million records. This is fewer than the number of PLP/DAPP records as there could be multiple PLP/DAPP records per child. Typically, there was one or two records per child but in rare cases there was more.

For detailed analysis of PLP and DAPP, the DOMINO data are entirely based on recipients of PLP and DAPP and the children the payment related to, so they do not provide insights on families that received neither of these payments. DOMINO data are also used for analysis of a broader population of families, in analysis of linked Census and DOMINO data, described below.

Census data

PLIDA includes unit record data for all individuals and families for the 2016 and 2021 Censuses. These datasets were accessed to identify children aged under one year at the time of each Census11, and to attach parental and family information to those records. This was appropriate for analysis related to PLP and DAPP for births before 1 July 2020, with leave entitlements needing to be used prior to the child's first birthday (or anniversary of adoption). For births or adoptions after July 2020, PLP may be used for children up to their second birthday (or adoption anniversary), but it is nevertheless expected that a focus on children aged under one year will capture the main population of potential PLP users.

This report draws on the Census data to describe the characteristics of families with a child under one year of age, including information on parents' employment, education, cultural diversity, age, location and so on.

- In 2016 there were 249,471 families with a child under one year of age, including 248,547 female parents and 220,370 male parents.

- In 2021 there were 268,881 families with a child under one year of age, including 267,512 female parents and 238,099 male parents.

Census-DOMINO linked data

Further analysis uses a derived file in which the Census and DOMINO data were linked. A key element of this was restricting DOMINO information to focus on receipt of DSS payments on Census night (2016 or 2021).12 This was done at the parent level, i.e., determining what payments the mothers and fathers of a child under one year of age were recorded as receiving at this time. Flags were derived that identified whether parents were receiving PLP or DAPP, or other kinds of DSS payments, at the time of the Census. Some analysis in the Appendix explores the correspondence between employment, as captured in the Census, and payment receipt from DOMINO.

The linked data were used to describe the characteristics of PLP/DAPP recipients, particularly for Census variables not available in DOMINO. A key variable available in the Census data was child age in months, and some preliminary analysis using this variable, along with the linked data, is presented in this research. As with the DOMINO data, child age in months at the Census is based on child year and month of birth, so is not an exact calculation. Access to Census-collected information about employment is especially relevant, but this will be the focus of a subsequent report.

3.2 Method

Much of the analysis presented is descriptive, drawing on the above datasets to examine:

- Characteristics of those using PLP or DAPP, comparing over time. At the broadest level, these characteristics are compared to characteristics of all families with a child under one year of age.

- Patterns of use of PLP and DAPP, including the timing of start and the number of weeks accessed overall, by financial year, and by selected demographics.

- Family and child-level analysis of timing and concurrent use of PLP and DAPP.

- How families are supported by payments other than PLP/DAPP across the first year of a child's life.

Some multivariate analysis is used to explore patterns of use of PLP and DAPP. Model results are presented in the Appendix with selected key findings in the main report.

6 The source of the DOMINO data was March 2023 updates but the analytical dataset was restricted by excluding those with a start date after 31 December 2022, with some of the administrative data in the first quarter of 2023 potentially incomplete or subject to change.

7 Using child date of birth in this analysis is problematic for PLP/DAPP recipients with adopted children, for whom date of birth may be earlier than the date of adoption. Numbers affected are expected to be very small. Also, as we only have month/year of birth, derivations and calculations that use date of birth are indicative rather than exact.

8 These derivations assume there is complete data about all children in DOMINO. It may not be the case, particularly for PLP/DAPP users at the beginning of the schemes, if families were not eligible for DSS payments around the birth of older children. Indeed, analysis of family size by financial year indicates data may be incomplete for the earlier financial years, with higher proportions classified as having only one child compared to more recent data.

9 At the time of analysis, this project did not have access to post June 2021 'combined location' and 'combined demographics' data. These 'combined' datasets are created by ABS to make available the best data on location and demographics from across multiple data sources in PLIDA.

10 The ATO data AIFS had access to at the time of analysis were current up to the 2019-20 financial year (and so is used for PLP/DAPP started in 2020-21). That is, income was not available for PLP/DAPP used in 2021-22 or later. When updated data are available, AIFS may repeat the analysis to include the more recent data. Ideally, information on Adjusted Taxable Income would be used, as this is used in determining eligibility for payments. However, this variable was not available on PLIDA. In later analysis, income of partner could also be matched from the ATO data.

11 While the Census aims to enumerate everyone in Australia, there is undercount in some groups. In the 2016 Census, ABS estimates that there was a net undercount of 5.1% for 0-4 year olds (see 2940.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Details of Overcount and Undercount, Australia, 2016 (abs.gov.au)). The undercount for 0-4 year olds was lower in 2021 (1.7%), but this was based on a changed approach compared to 2016 (see 2021 Census overcount and undercount, 2021 (abs.gov.au)) .

4 Overall numbers using PLP/DAPP

4.1 Recipient numbers from DOMINO

Counts of PLP recipients and DAPP recipients are shown in Table 1. Estimates from PLIDA are presented according to the financial year in which the period of payment commenced. The PLIDA estimates differ slightly to those published in DSS annual reports (also shown), likely explained by the different timing of accessing the administrative data and different methods used to define the population.

The number using PLP trended upwards in the early years of its introduction and has generally remained around 170,000 recipients in more recent years. This compares, for example, to 309,996 births in 2021, as reported in Qu and Baxter (2023b). To some extent the difference between these two numbers reflects that some new mothers have no recent connection to employment, meaning they are not eligible for PLP but may instead be eligible for other forms of support (see PLP and other DSS payments section).

| Financial year payment started | PLP | DAPP | DAPP as % of PLP | Children supported by PLP or DAPPd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From PLIDAb | DSS Reportsc | From PLIDAb | DSS Reportsc | From PLIDA | From PLIDA | |

| 2010-11 | 47,679 | 43,000 | -- | -- | -- | 47,572 |

| 2011-12 | 126,168 | 124,397 | -- | -- | -- | 125,693 |

| 2012-13 | 132,436 | 130,623 | 33,189 | 26,212 | 51.4 | 148,388 |

| 2013-14 | 147,881 | 144,255 | 76,071 | 72,975 | 45.3 | 169,145 |

| 2014-15 | 161,827 | 158,974 | 73,290 | 70,785 | 46.6 | 179,314 |

| 2015-16 | 168,714 | 170,501 | 78,601 | 79,126 | 48.8 | 187,311 |

| 2016-17 | 169,227 | 170,925 | 82,540 | 83,600 | 50.6 | 188,348 |

| 2017-18 | 166,118 | 159,372 | 84,117 | 81,882 | 52.0 | 186,307 |

| 2018-19 | 171,690 | 178,758 | 89,253 | 91,762 | 53.0 | 191,825 |

| 2019-20 | 169,807 | 171,712 | 90,061 | 92,343 | 53.3 | 189,014 |

| 2020-21 | 173,067 | 169,029 | 92,307 | 89,784 | 54.3 | 194,237 |

| 2021-22 | 183,424 | 178,778 | 99,560 | 97,863 | 51.4 | 202,983 |

| 2022-23a | 89,261 | 45,247 | 50.7 | |||

Note: aExcludes payments started after December 2022. bThe PLIDA count is the number with a start date in the financial year. cDSS reports count recipients who started receiving payments in the financial year. DSS figures for 2017-18 and 2018-19 were impacted by processing delays that occurred in the 2017-18 entitlement year. dChildren are classified by the first start date of parents' PLP or DAPP use.

Source: PLIDA analysis and DSS/FaHCSIA Annual Reports. PLIDA extract based on March 2023 data release.

In each year, the number of DAPP recipients is about half the number of PLP recipients. The number using DAPP has also trended upwards since its introduction.

The number of children supported by either PLP or DAPP each financial year is also shown in Table 1, being higher than the PLP number from 2012-13 as children may be supported by fathers taking DAPP even when mothers do not take PLP (later analysis will explore this).

4.2 Numbers and proportions at Census

Overall percentages

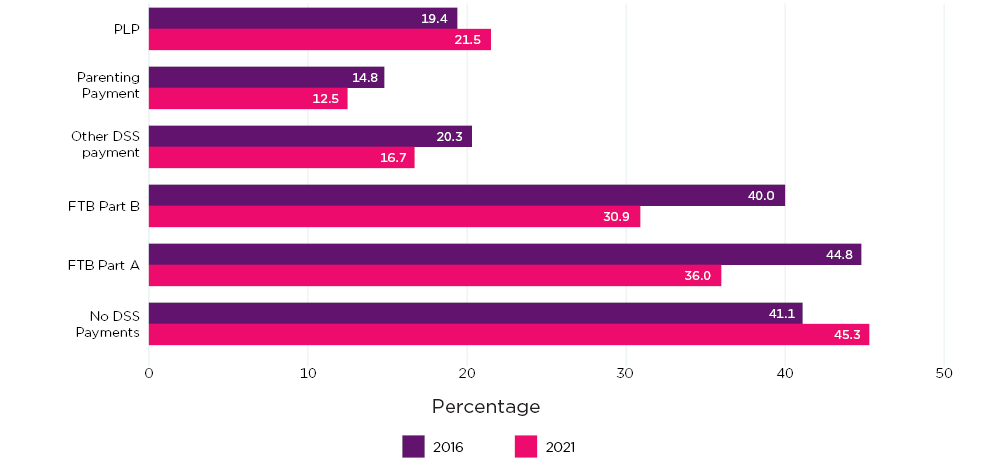

Using the linked Census-DOMINO data that focuses on families with a child under one year of age at the time of each Census:

- Of mothers of a child under one year of age in 2016, 48,733 (19%) were receiving PLP. Of the fathers, 2,078 (1%) were receiving DAPP, and a much smaller number were receiving PLP (129, 0.1%).

- Of mothers of a child under one year of age in 2021, 57,548 (22%) were receiving PLP. Of the fathers, 2,420 (1%) were receiving DAPP, and a much smaller number receiving PLP (473, 0.2%).

The much lower percentage for fathers compared to mothers to some extent reflects the lower likelihood of detecting fathers on DAPP with a duration of 2 weeks relative to the 18 weeks for mothers.

These linked data are, of course, a subset of those receiving PLP or DAPP over the relevant financial years. The identification of 'receiving PLP' (or DAPP) is based on the Census date falling between the start and end date of a period of PLP. From 2020, with the introduction of Flexible Paid Parental Leave, some people had an elapsed time on PLP, between start and end date, of greater than 18 weeks, which appears to be related to their breaking their PLP use into more than one block. Data used to date do not identify receipt, or not within this elapsed time. It is likely that some of those identified as 'receiving PLP' at the time of the Census were between blocks of PLP use, and not receiving PLP at this time, so to adjust for this, those currently on PLP but with an elapsed duration of greater than 18 weeks were reset to be classified as not receiving PLP in the above estimates. While this might undercount those using it at later periods after the child's birth, it avoids the overcounting that would otherwise occur overall. The original unadjusted number was 62,345 (23% of mothers).13

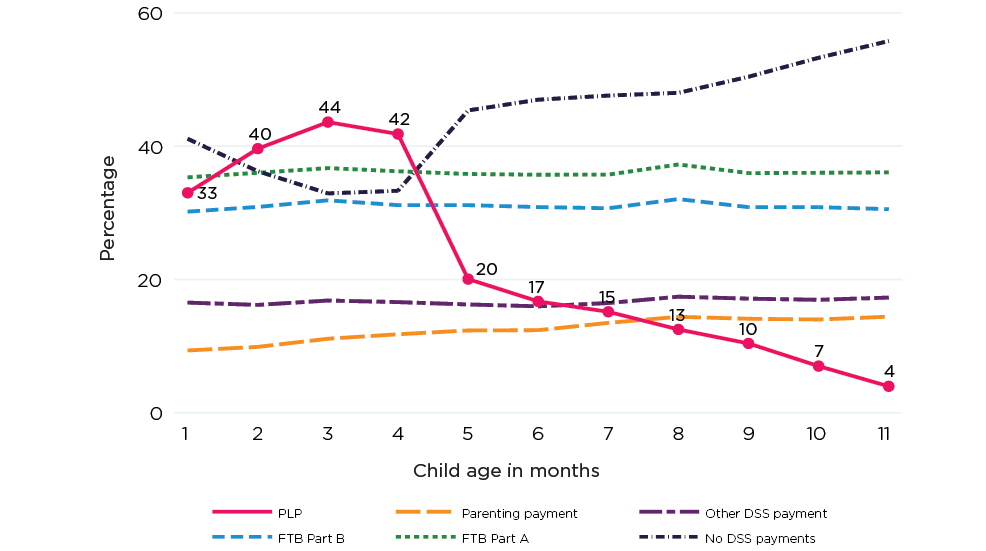

PLP use by age of child in months

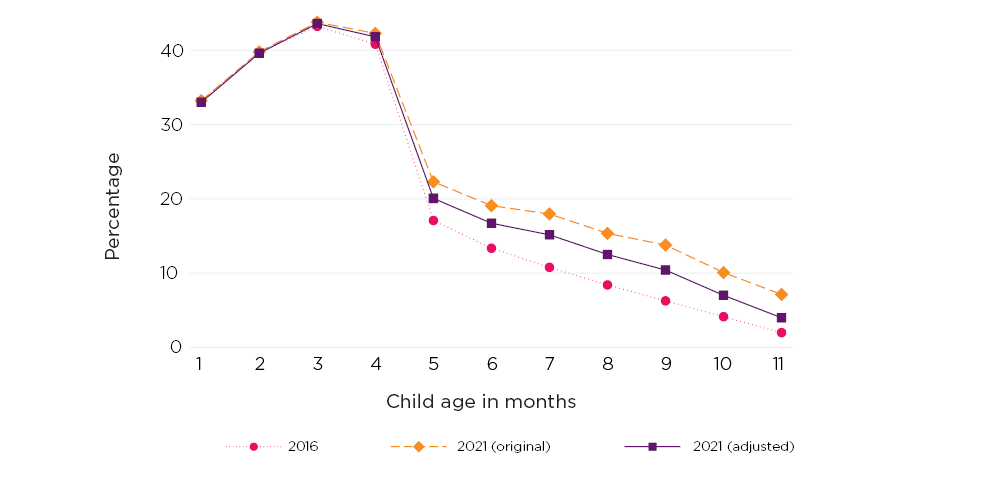

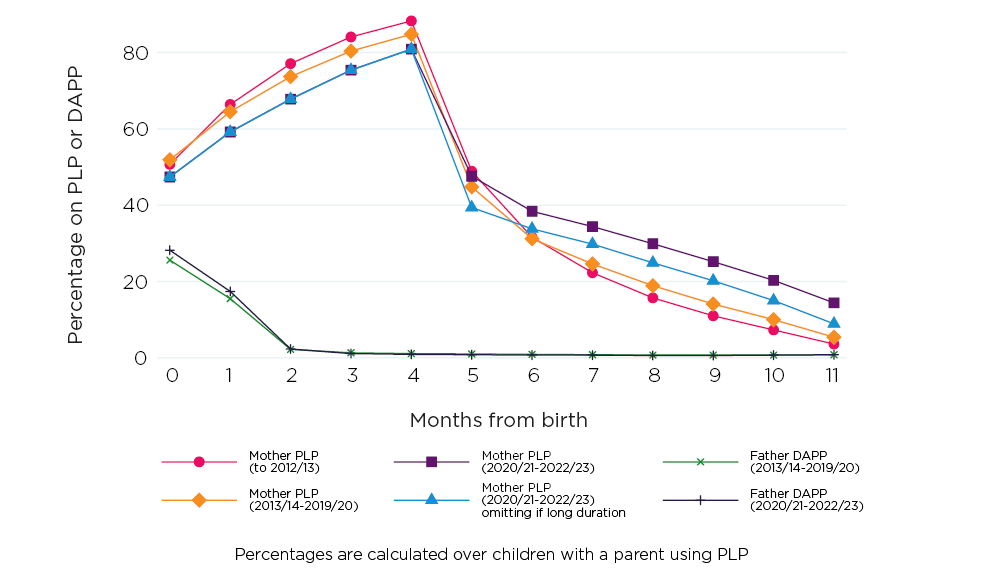

An advantage of analysing these data with the linked Census-DOMINO data is that the approximate age of the under-one-year old, in months, is available for all the population.14 Figure 1 shows the proportion of mothers receiving PLP by child age in months, for 2016 and 2021. These statistics are also reported in Appendix Table 1.

In both 2016 and 2021, Figure 1 shows that mothers were most likely to be receiving PLP when their youngest child was 2-4 months old, with 40-44% of mothers receiving PLP at this time. Also, 33% were receiving PLP when their youngest child was up to one month old.

The proportion receiving PLP dips considerably from about the 5th month, and at this time there are some differences between 2016 and 2021 results. In 2016, 17% were receiving PLP at the 5th month, and in 2021 this was 22%, or 20% after excluding those on PLP for more than 18 weeks. By the 9th month, 6% were receiving PLP in 2016 and 10% in 2021, using the adjusted estimate.

The very marked similarity of findings for 2016 and 2021 in the early months suggests there has been little change in the take-up of PLP among mothers wanting to use it straight after a birth. The higher rates for 2021 at later months may indicate that the increase in the proportion using PLP overall relates to mothers who use PLP later, probably after a period of employer-funded leave. As discussed later in the report, this may reflect increasing access to and use of employer funded parental leave by mothers, while there continues to be a proportion of mothers without access to employer funded leave who use PLP immediately after the birth.

Similar statistics were not produced for fathers and DAPP, given the smaller incidence of receipt overall. However, at child age of up to one month, it was estimated that 7% of fathers were receiving DAPP in 2016 and 5% in 2021. Percentages were under one percent for other ages.

Figure 1: PLP use is most likely when children are aged 2-4 months

Proportions of mothers of under one-year olds receiving PLP, by age of youngest child in months, 2016 and 2021

Notes: 2021 data are shown twice, one (original) and the other (adjusted) in which the indicator for PLP receipt for mothers who had been on PLP for more than 18 weeks reset to zero. Child age in months is approximate as it was derived from child birth date set to the first of the month for all children. These statistics are also reported in Appendix Table 1.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023, linked to 2021 Census.

4.3 Mothers' PLP in context with employment

Before moving on to an examination of which parents are using PLP and DAPP, we briefly put the above PLP information, by child age in months, into a broader context to show how this relates to the patterns of maternal employment that occur in this first year after a birth. Analysis of ABS labour force data by AIFS shows that for mothers of under-one-year olds, there is variation in the degrees of connection to employment within this cohort, and there have been significant changes in recent decades with mothers more likely to be employed, and in particular to be employed but away from work (see Baxter (2023)).).

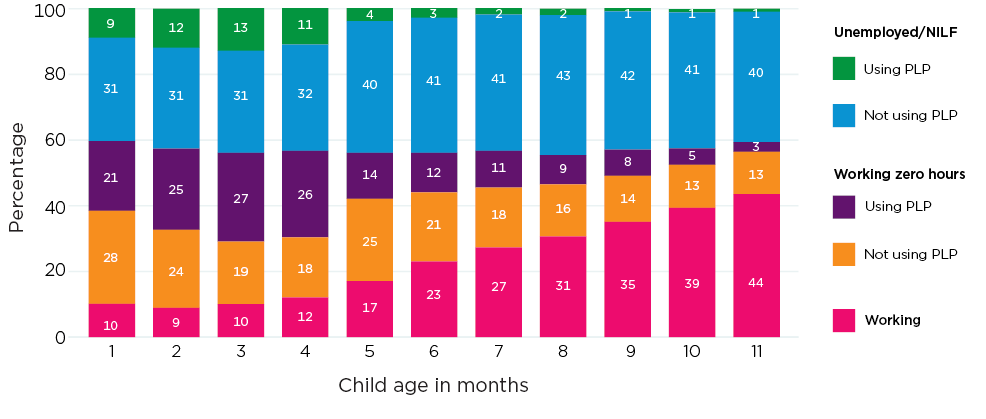

Figure 2 shows that at the time of the 2021 Census:

- Across all months, around 4 in 10 mothers were not employed - they were unemployed or not in the labour force. Some of these mothers were using PLP. While eligibility for PLP requires mothers to have met a work test, it is possible that some mothers will have resigned or consider themselves to have stopped working, so when asked about employment in the Census, they reported that they did not have a job. This could be especially relevant for mothers who had previously worked in casual and/or short-term jobs, who in fact may have returned to work, but not be working at the time of the Census. The proportions of mothers who were not employed and receiving PLP was less than those of mothers employed and receiving PLP.

- Across all months, about 6 in 10 mothers of under-one-year olds were employed. Few mothers with a child aged under one, two or three months reported being employed and working more than zero hours (around 10%) but this then increased month on month to reach 44% by the time the youngest was 11 months.

- Among mothers employed but working zero hours, some were supported by PLP and some were not. Those not supported by PLP may have been receiving paid leave from their employment (as might those using PLP), but some may have been on an unpaid period of leave.

In deriving these data, mothers working more than zero hours were classified into this one group, rather than separating into those receiving PLP or not. With the introduction of Flexible PLP, it is possible for mothers to have returned to work and be using the PLP to support a part-time return to work. However, this is not examined here, as the administrative data require further analysis to determine whether mothers who had returned to work were concurrently using PLP or were instead banking up PLP for later use. See Appendix Table 2, about 6,000 mothers reported to be working part-time or full-time hours and were also classified as receiving PLP. This is after removing those with elapsed time on PLP of more than 18 weeks.

Figure 2: Employment grows by age in months as PLP receipt declines, but many are not working and not using PLP at younger ages

Employment and PLP among mothers of under one-year olds, by age of youngest child in months, 2021

Notes: The indicator for PLP receipt for mothers who had been on PLP for more than 18 weeks reset to zero. NILF is Not in the labour force. Child age in months is approximate as child birth date was set to the first of the month for all children.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023, linked to 2021 Census.

Later analysis with these data, in a subsequent report, will explore these patterns further, by personal and family characteristics, as well as job characteristics. See also Employment patterns and trends for families with children for some more analysis of Census data, across a number of Census years, showing the trends for mothers of under-one-year-olds.

4.4 Summary

The number of recipients using PLP trended upwards in the early years of its introduction and has generally remained around or just under 170,000 in more recent years. The number of DAPP recipients has also trended upwards at about half of the number of PLP recipients each year.

As a proportion of all families with a child under one year's old at the time of the 2021 Census, just over one in five mothers (22%) were using PLP, which was an increase from the estimated 19% at the 2016 Census. In both Census years, the proportion of fathers using DAPP was around one percent. As DAPP is a 2-week payment compared to the 18 weeks for PLP, it would be expected that fewer fathers would be observed to be on DAPP at any point in time relative to mothers receiving PLP.

There were marked differences in the proportion of mothers using PLP according to the age, in months, of their child under one year of age. These differences were related to the employment patterns of mothers, with many away from work with a newborn.

In 2016 and 2021, mothers were most likely to be receiving PLP when their youngest child was 2-4 months old (40-44% of mothers receiving PLP) or up to one month (33% of mothers receiving PLP). The proportion of mothers receiving PLP is considerably lower from the 5th month, but comparisons between 2016 and 2021 indicated there were more mothers receiving PLP in these later months in 2021. As mothers starting PLP later are likely doing so following a period of employer-funded leave, this higher proportion at later months in 2021 may reflect the gradual growth in the availability of this leave, or possibly reflect an increase in mothers making use of such leave to support their connection to employment.

13 That is, 7.65% of those on PLP at 2021 had a duration greater than 18 weeks. Some analysis in this report is based on unadjusted numbers. For example, the analysis in section 5 of characteristics of PLP and DAPP recipients is based on the unadjusted population of PLP recipients.

14 Age is approximate as child date of birth is only available as year and month of birth.

5 Characteristics of PLP and DAPP users

5.1 Introduction

This section steps through some personal and family characteristics, to describe the characteristics of those using PLP and DAPP, with comparisons to the broader population of new parents (that is, parents of a child under one year of age) where possible.

Analysis of regional information (State /Territory and remoteness) for PLP/DAPP recipients revealed no particular trends, and no marked differences in distribution compared to that of new parents overall. Findings are therefore included in Appendix Table 3 and Appendix Table 4.

5.2 Gender and relationships

PLP - gender and parental relationship

Given the eligibility requirements for PLP, it is not surprising that almost all the PLP recipients are female. Across all financial years, the average percentage female was 99.5%. This is consistent with the findings of the DSS (2015) review in which it was reported that more than 99% of PLP recipients in 2012-13 were female.

The majority of PLP recipients have a partner (95.4% in the pooled data across all years), so the majority of recipients are females with a partner (94.9%).15 DSS (2015) reported that of all parents who received PLP in 2012-13, 94.8% were partnered, and the data in PLIDA indicate the proportions have changed little year by year.

Looking further at the relationship data, Table 2 shows:

- Most PLP recipients are females with a male partner.

- While few in number compared to the female PLP recipients, there were more than 9,400 cases of the PLP recipients being males with a female partner. Further analysis of couple-level data indicated that in almost 70% of these cases, the female partner had also taken the PLP, so a portion of the PLP was transferred to the male.16 The remaining cases (about 30%) reflected when the father received PLP but the mother did not.

- Smaller numbers of recipients were single females (4.7% across all years), with smaller numbers again of females with a same-sex partner having received PLP. The numbers of males with a same-sex partner and single males accessing PLP since its introduction have been very small.

| Relationship | Percent | Number of PLP episodes |

|---|---|---|

| Female with male partner | 94.3 | 1,798,279 |

| Male with female partner | 0.5 | 9,404 |

| Single female | 4.7 | 90,055 |

| Female with female partner | 0.5 | 8,871 |

| Male with male partner | 0.0 | 441 |

| Single male | 0.0 | 227 |

| Total | 100.0 | 1,907,277 |

Notes: This is number and distribution of episodes, so if PLP is shared between parents for one child, it is counted once for each parent. Excludes those with start date after December 2022.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023.

According to the Census, as with PLP recipients, the vast majority of families with a child under one year of age were opposite-sex couple families (89% in 2016 and 88% in 2021). The next largest group was single mothers (10% in 2016 and 11% in 2021), with around one per cent in total across other categories (single fathers, same sex couples).17 The higher proportion of infants living with a single mother in the population, relative to the PLP recipients, is likely to reflect a lower employment rate among single parents (even before they were pregnant with the PLP/DAPP child). See Appendix Table 6 for employment status of single and couple mothers at the time of the 2021 Census, and Appendix Table 7 shows that single mothers were more likely to be receiving Family Tax Benefit or a Parenting Payment at the time of the census compared to couple mothers (66% compared to 22%).

Taking a broader view using the linked 2021 Census-DOMINO, of families with a child under one year of age and a female parent, 62,345 (23%) of the female parents were receiving PLP on Census night. This PLP receipt calculation is based on the unadjusted indicator of PLP receipt, so includes those recorded as having received PLP for more than 18 weeks. For couple parents, the proportion was 25% and for single parents the proportion was 13%. See Appendix Table 7, indicating partnered mothers were much more likely than single mothers to be receiving no DSS payments at the time of the Census. We note that parents may also have been receiving financial support via the Child Care Subsidy, if using child care, but this subsidy is not included in this analysis.

DAPP - gender and parental relationship

The eligibility criteria for DAPP (see 'Dad and Partner Pay' section) leads to a very gendered distribution for this payment also. Across all episodes of DAPP to June 2021, 99.5% of recipients were male. This has varied little over the years.

Also, the majority of DAPP recipients are partnered males (97.9% in the data pooled across years). Of the balance, most are single fathers (1.6%). A very small percentage (0.5%) are partnered females, and further examination of these data finds that these cases are among females in same-sex relationships.

Using the linked Census-DOMINO data, of families with a child under one year of age and a male parent, 2,078 were receiving DAPP on Census night in 2016 and 2,420 in 2021. In both years this was about one percent of fathers. Almost all of these were opposite-sex couple parents.

5.3 Family relationships and size

PLP and DAPP - parent-child relationship

According to the analysis of Census data, the vast majority of children under one year of age are living with a natural or adopted mother (98% in 2016 and 96% in 2021). The percentages are even higher when subset to those families in which the mother is receiving PLP at the time of the Census (99% in 2016 and 97% in 2021). For DAPP recipients, according to the analysis of linked Census-DOMINO data, almost all DAPP recipients at 2016 and 2021 were natural or adopted fathers.

Consistent with this, the DSS (2015) review, reporting on characteristics among PLP recipients in 2012-13 found that 99.4% were birth mothers, 0.4% were the partner of birth mothers, 0.1% were adoptive parents (or partner of adoptive parent) and 0.1% fell into other categories. Information about the relationship between the PLP or DAPP recipient and the child was not available in PLIDA.

Family size and repeat use of PLP

Among under-one-year-olds in the 2021 Census, 44% had no siblings (aged under 15 years), 1.4% had at least one other sibling also aged under one year and 55% had a sibling aged between 1 and 14 years. Overall, 37% had one sibling and 20% had 2 or more siblings. Findings for 2016 were very similar.18

Given the relationship between parenthood and mothers' employment (e.g. New mothers staying connected to the workforce), women having a first child are more likely to be employed in the months leading up to the birth than are those having a second or subsequent child. It is therefore expected that for PLP, first time mothers are more likely to meet the work test and will be over-represented within the population of PLP users compared to the broader population of mothers.19

This association between family size and use of PLP is apparent in the linked Census-DOMINO data. For 2021, of mothers of a child under one year of age, who have only one child, 26% were using PLP at the time of the Census, compared to 24% for those with 2 children and 17% for those with 3 or more children aged under 15 years (see Appendix Table 7).

A different perspective to this is to what extent mothers have used PLP multiple times, for subsequent births. By 2021-22, 9% of PLP recipients were using it for their third (or later) time, as their families grew, with 33% using it for the second time.

Family size and repeat use of DAPP

In recent years, about 58% of DAPP users were using it for their first child, 32% for the second child and 10% for a third or later child. By 2020-21, 61% of DAPP recipients were using it for the first time, 34% were using it for the second time, and another 5% using it for their third (or later) time. (See footnote 18 about derivation of family size.)

Multiple births

The incidence of multiple births among PLP and DAPP recipients is very low. Across all the incidences of PLP use, the child was one of a multiple birth in 1.3% of families, and for DAPP, the child was one of a multiple birth in 0.9% of families.20 As noted above, according to the 2021 Census, 1.4% of under-one-year olds had at least one sibling also aged under one years. Parents of multiple births can access PLP and/or DAPP in respect to one of the children - there is no additional PLP/DAPP for multiple children. However, parents who meet the eligibility criteria can apply for the Newborn Upfront Payment and Newborn Supplement in respect to the siblings of the child that PLP/DAPP is claimed for. Further analysis that incorporated information on these payments found that 59% of PLP recipients (or their partner) with a multiple birth received the Newborn Upfront Payment and/or Supplement.

5.4 Parents' age

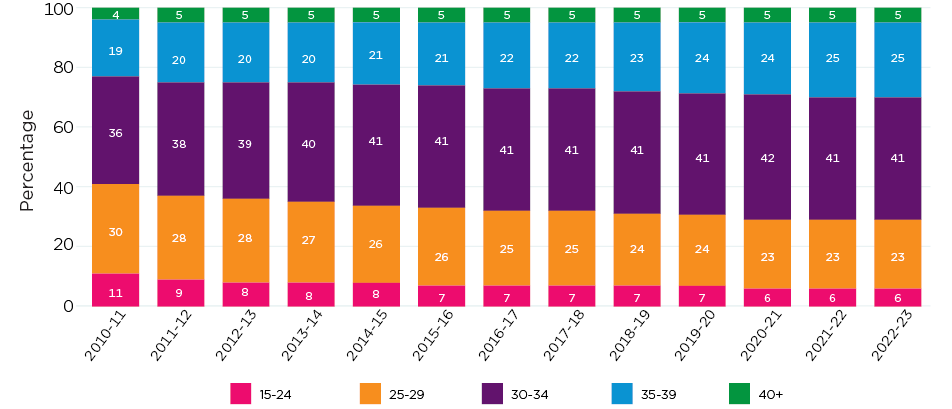

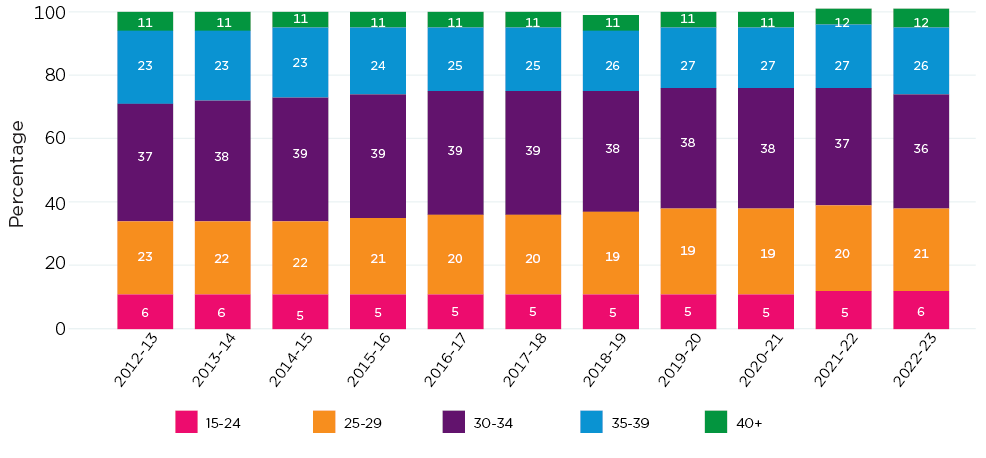

The median age of mothers of under-one-year olds was 31 years in 2016 and 32 years in 2021.

- At 2016, 10.4% of new mothers were aged under 25 years, 25% were aged 25 to 29 years, 37% aged 30-34 years, 21% aged 35-39 years, and 6.7% aged 40 years and over.

- At 2021, 8.0% of new mothers were aged under 25 years, 23% were aged 25 to 29 years, 38% aged 30-34 years, 24% aged 35-39 years, and 6.6% aged 40 years and over.

The median age of PLP recipients (pooled across years) is the same as the 2021 median from the Census, at 32 years. Figure 3 shows that the distribution, by age group, is also similar to that of new mothers in the Census, although the PLP users are more often in the largest group, of 30-34 year olds. There has been little change in the median age (in whole years) for PLP users across financial years, although Figure 3 suggests that the distribution has shifted a little toward older mothers.

The under-representation of the youngest mothers in the PLP recipients likely reflects the employment rate in this group being lower, even before the birth of the first child. At the time of the Census, there are marked differences in employment rates by age of mother, especially for the youngest mothers. See Appendix Table 6. This is also reflected in lower percentages using PLP among the youngest mothers (15%), see Appendix Table 7.

Figure 3: The peak age for mothers is 30-34, with more 35-39 year olds receiving PLP than 25-29 year olds in recent years

Mothers' age at commencement of PLP, by financial year of PLP commencement

Note: This is based on episodes of PLP. Excludes those with start date after December 2022.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023

Figure 4: The peak age group for fathers using DAPP is 30-34

Fathers' age at commencement of DAPP, by financial year of DAPP commencement

Note: This is based on episodes of DAPP. Excludes those with start date after December 2022.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023

At 2016 and 2021, the median age of fathers of under-one-year olds in the population was 34 years. The median age of fathers using DAPP is 33 years and Figure 4 shows that among DAPP recipients, the peak age group for receipt of DAPP is at 30-34 years. The proportion aged 35-39 years has been higher in the last five or so years compared to the years immediately following the scheme's introduction.

5.5 Parental education

Mothers' education and PLP

Highest level of educational attainment is typically strongly associated with patterns of employment, with weaker labour force participation among those with lower levels of educational attainment. See this association for the 2021 Census, for mothers, in Appendix Table 6. However, as higher education levels are likely to equate to higher incomes, among employed mothers, those with lower levels of education may more often be using PLP as those with the highest incomes will not be eligible. Those with higher levels of education may also have better paid leave arrangements through their jobs, although mothers with good paid leave conditions may still use PLP if their income does not preclude their eligibility. Use of PLP is expected to be greater among those with higher levels of education, given the association between education and employment, but as noted here, these other factors may dampen these differences somewhat.21

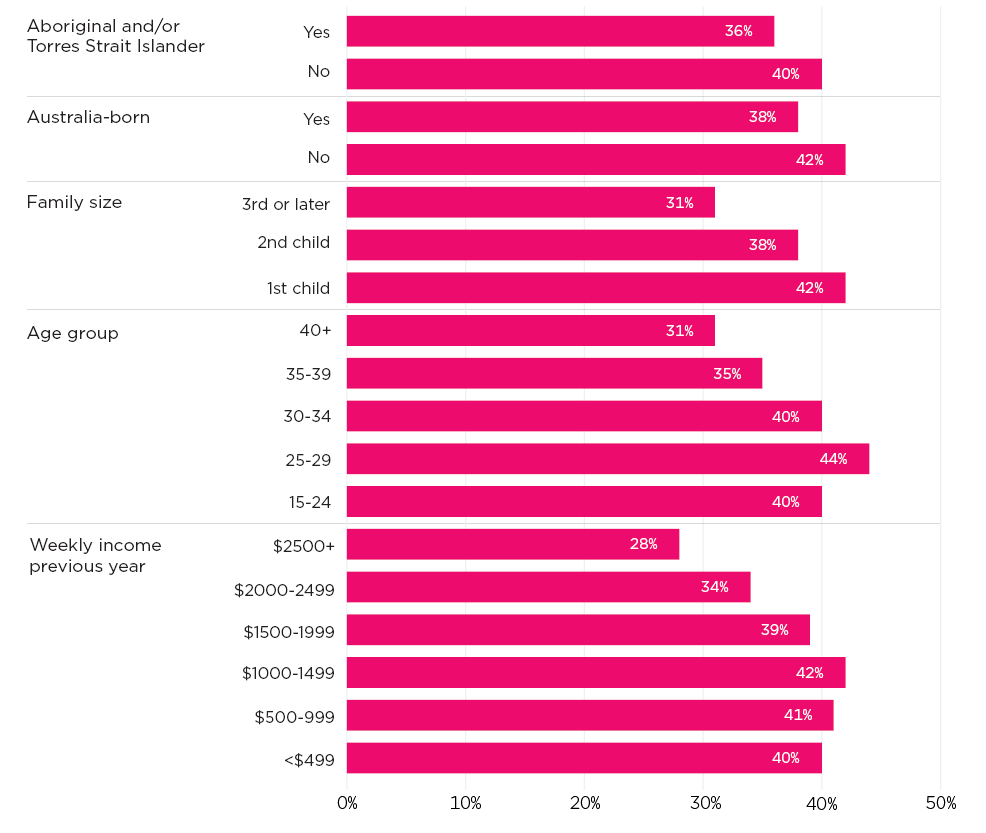

Looking from the perspective of mothers with a child under one year of age at the time of the 2021 Census, among those with incomplete secondary education, 10% were receiving PLP, of those with completed secondary education only, 19% were receiving PLP, and 25-26% of those with a certificate/diploma, bachelor degree or higher were receiving PLP. See Appendix Table 7.

These differences mean that among mothers of children aged under one year who were receiving PLP at the time of the Census, education levels were somewhat higher compared to education levels for all mothers. Among PLP users 4% had incomplete secondary education; 11% had complete secondary education only; 34% had completed a certificate or diploma; 48% had a bachelor degree or higher, with 3% missing information. This compares to the distribution for all mothers of under one-year-olds in 2021: 9% had incomplete secondary education; 13% had complete secondary education only; 31% had completed a certificate or diploma; 43% had a bachelor degree or higher, with 4% missing information.

In subsequent work with these data, we will explore how patterns of PLP use vary by education as well as age of child.

Fathers' education and DAPP

Differences in DAPP use by fathers according to educational attainment are expected to some extent, although fathers cannot use DAPP when on paid leave from employment. If employers do not top up DAPP to usual salary, then higher earning fathers (as is typically associated with higher education) may be less likely to take DAPP, in addition to the income test precluding some. Among fathers of under-one-year olds in 2021, the distribution of highest levels of educational attainment were: 9.5% had incomplete secondary education; 12% had complete secondary education only; 40% had completed a certificate or diploma; and 34% had a bachelor degree or higher, with 4% missing information. The distribution for those receiving DAPP at the time of the Census was somewhat different, with the proportion with a certificate or diploma (47%) higher than in the population and the proportion with a bachelor degree or higher (31%) lower than in the population. Another 7% had incomplete secondary and 13% completed secondary education. These findings may reflect differential access to paid parental leave through employment in different industries and will be explored further in later work.

5.6 Overseas-born parents

Overall, 71% of PLP recipients were Australian-born, with this percentage varying a little over the years. Also, among mothers receiving PLP at the time of the 2021 Census, 71% were Australian-born. These percentages are higher than the percentage of new mothers in the Australian population (63% of mothers of under-one-year olds in 2021. This reflects that there are higher employment rates among Australian-born mothers (see Appendix Table 6 and Appendix Table 7). It may also reflect a greater awareness of PLP among Australian-born mothers.

Across all incidences of DAPP, 66% were Australian-born recipients. Among fathers receiving DAPP at the time of the 2021 Census, 69% were Australian-born. This compares to 62% of fathers of under-one-year olds in 2021. As for mothers, some of2 this is related to different employment rates among fathers according to whether they are Australian-born.22

5.7 Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander parents

The percentage of PLP recipients that are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander is 2.2%, with all years combined. This percentage within PLP recipients is lower than the percentage that is Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in the Census (3.2% of mothers in 2016 and 3.7% of mothers in 2021), as above likely reflecting the lower employment rates of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander mothers (see Appendix Table 6 and

Appendix Table 7).

The percentage of DAPP recipients that are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander is similar to the percentage for mothers, at 2.1%. This proportion is not greatly different to the percentage of fathers that are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in the Census (e.g., 2.3% in the 2016 Census).

5.8 Income - personal income

The income test for PLP and DAPP (see Box 1) means that those with a personal income above the cut-off point (annual income around $150,000) will not be eligible for these payments. The income test is based on individuals' adjusted taxable income in the previous financial year. With this specific income measure not available in PLIDA, the following analysis uses ATO income data. The measure used is the total financial year payment (total income or loss), for the financial year before the PLP or DAPP commences. At the time of doing this analysis, the ATO data were available up to the 2019-20 financial year, so they cover PLP/DAPP used up to, and including, the 2020-21 financial year.

Table 3 presents previous financial year income for DAPP and PLP users. The median is higher for DAPP recipients than PLP recipients, with 27% of PLP recipients and 14% of DAPP recipients (pooled across years) having had incomes below minimum wage in the financial year before they started payment.

The lower incomes for PLP recipients reflect the effects on income of women reducing time in employment after the birth of a first or later children. As seen in Figure 4, using recipients starting PLP in 2020-2021 as an example, those starting PLP for a first child had much higher median incomes the year before, compared to those using PLP for a second or subsequent child. For DAPP recipients, these differences are not apparent.

| Year | PLP | DAPP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median ($ annual) | % below NMW | Median ($ annual) | % below NMW | |

| 2011-12 | 54,140 | 24.0 | N/A | N/A |

| 2012-13 | 54,792 | 23.3 | 63,923 | 16.0 |

| 2013-14 | 53,393 | 25.4 | 65,330 | 14.3 |

| 2014-15 | 52,156 | 27.6 | 64,762 | 14.1 |

| 2015-16 | 52,425 | 27.6 | 65,438 | 14.2 |

| 2016-17 | 52,819 | 28.0 | 65,963 | 14.6 |

| 2017-18 | 52,260 | 29.0 | 66,152 | 15.0 |

| 2018-19 | 52,724 | 29.4 | 67,443 | 14.6 |

| 2019-20 | 54,413 | 28.0 | 69,178 | 13.6 |

| 2020-21 | 54,140 | 26.1 | 70,636 | 11.9 |

| Pooled | N/A | 27.0 | N/A | 14.1 |

Notes: Income was adjusted by CPI to be in 2020-21 dollars. The NMW (National Minimum Wage) weekly amount was multiplied by 52 to calculate an annual equivalent for comparison to annual income for the same year (before CPI adjustment). While the ATO income data is different to the Adjusted Taxable Income (ATI) used to assess eligibility, these findings are broadly consistent with DSS-reported income data on PLP recipients. The 2014 review report found that the median ATI among PLP recipients was $44,350 in 2011-12 and $47,000 in 2012-13. They also reported that 27% had ATI below NMW in 2011-12 and 25% in 2012-13.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023 and ATO data to 2019-2020

Figure 5: PLP recipients' income is strongly related to number of children

Median financial year income and percentage with incomes below National Minimum Wage in 2019-2020, parents starting PLP or DAPP in 2020-2021.

Notes: NMW is National Minimum Wage. See other notes on Table 3.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023 and ATO data

5.9 Summary

The majority of PLP recipients are females with a partner. Of the very small number of cases in which the PLP recipient was male with a female partner (0.5% of all episodes of PLP), in 70% of cases it appeared that part of the PLP had been transferred to the male from a female partner also having used PLP.

Comparisons between the PLP recipient characteristics and families with an under-one-year old at the 2016 and 2021 Censuses revealed some differences, that typically reflected there being a greater connection to employment among some cohorts of mothers. Those groups with lower levels of labour force participation were under-represented in the population of PLP recipients. This included single mothers, mothers with larger families, younger mothers, mothers with lower levels of educational attainment, and overseas-born and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander mothers.

The analysis in this report does not include job characteristics. There is variation across the labour market in the availability of employer-provided paid parental leave and it is likely that PLP would be especially valued by those mothers without employer-funded leave. However, as PLP can be taken by mothers while they are on leave from employment, these differences in job characteristics may matter less to whether mothers take PLP, and more to when that PLP is taken.

With regard to DAPP, almost all recipients were partnered males (98%). As for mothers, there were some differences in use of DAPP by some of the characteristics examined. DAPP differs to PLP in that it cannot be used while on employer-funded leave. Some findings, such as the relatively high incidence of fathers with certificate or diploma qualifications, may reflect that these fathers are likely to be in industries that have lesser access to paid parental leave.

The analysis of income shows the differences between mothers' and fathers' incomes, comparing PLP and DAPP recipients. It also shows the impacts of having a larger family size on the incomes of PLP recipients. At this stage, take up of PLP by pre-birth income has not been analysed. This will be explored in a subsequent report using these data.

15 This information is derived from recipients' relationship status, with the analysis incorporating partners' gender undertaken by linking partner demographics (such as gender) to the recipients' information.

16 See Transferring your Parental Leave Pay for a child born or adopted before 1 July 2023 - Parental Leave Pay for a child born or adopted before 1 July 2023 - Services Australia for guidelines about sharing PLP.

17 These estimates are slightly different to those reported earlier in the publication, which is due to having used different datasets in the calculations.

18 Around the same time as the 2016 Census (2016-17 financial year) among parents using PLP, 54% were using PLP for their first child. This is consistent with expectations that first-time mothers would be over-represented among PLP recipients. In particular, the proportion using PLP for a 3rd or later child was lower (12%) compared to the proportion of under-one-year olds in the Census with 2 or more siblings (20%). Analysis by family size using DOMINO draws on data on all children in DOMINO, for PLP and DAPP users. It is possible that this information is incomplete if parents received no payments from Services Australia in respect to those children. Since about 2017-18, about 51% are first-time mothers, about 35% second-time mothers and 14% using PLP for their third or later child. In 2011-12, based on the DOMINO data, these percentages were 72%, 26% and 2% respectively. Similar differences occurred in exploring family size for DAPP recipients, with the majority in 2012-13 and 2013-14 (84%) having only the one child's data in the database. This changed considerably over subsequent years.

19 While data are not available on employment before the birth, the relationship between family size and employment is apparent. See summarised data in Appendix Table 1.

20 This assumes that, in the case of multiple births, other children's details are recorded with Services Australia. The data may be incomplete.

21 Educational attainment in DOMINO is missing for most PLP and DAPP recipients, so the Census data on educational attainment is used in this section.

22 At 2021, 94% of Australian-born fathers were employed compared to 88% of overseas-born fathers.

6 How PLP and DAPP are used

6.1 When do parents start on PLP and DAPP?

PLP commencement

There is expected to be some variation in when PLP is accessed. Mothers with paid leave provided through their employment may take this paid leave first, and then use PLP to fund a period of leave that would otherwise be unpaid, should they wish to take a longer period of leave than is covered by their employer-provided paid leave. Others may choose to receive PLP while they are also receiving a paid leave entitlement from their employment. Those without paid leave from their employment would be expected to take PLP as soon as eligible after the birth.

Timing of commencement could not be derived accurately, as child age is recorded in PLIDA with only year and month, not the specific date. The following analysis is based on calculations that use the date of birth being the first day of the month, and timing is derived as the number of days between this date and the start of PLP and DAPP.

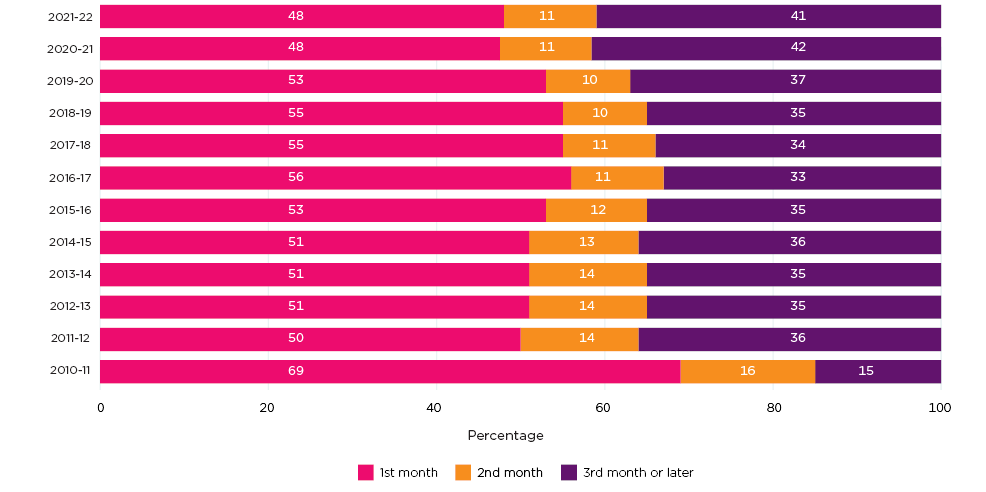

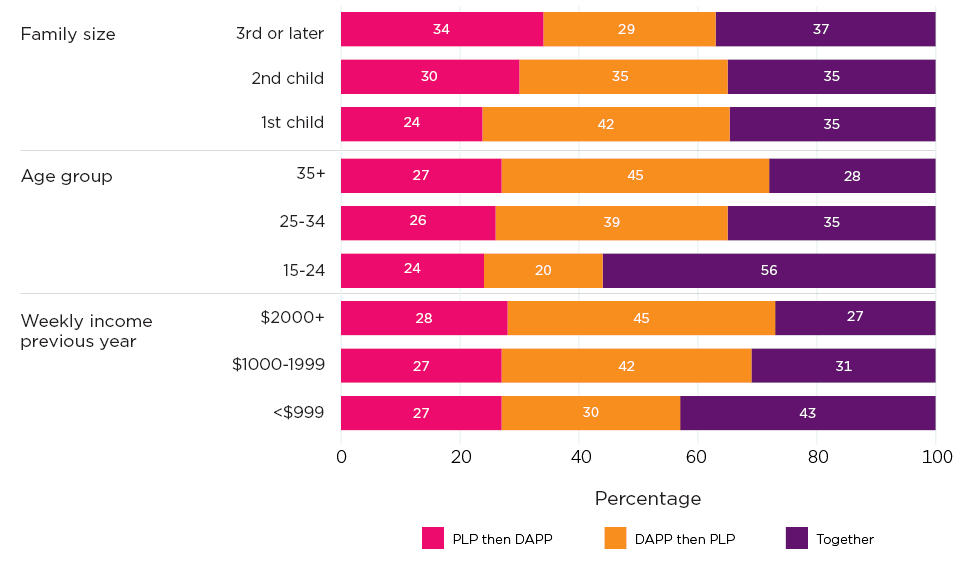

Across all data from 2010-11 to 2019-20, using the child's date of birth as described above, the median timing of PLP commencement was the first month after the child's birth. In 2020-21 and 2021-22, the median had slightly shifted to be the second month. Figure 6 shows the start time in more detail. Since the introduction of PLP, around one in two mothers started PLP in the first month after the birth, with this proportion declining in more recent years.23 The proportion starting PLP in the third month or later has increased since the scheme's introduction, with 41% starting at this time in 2021-22, compared to 36% ten years earlier. This change may indicate impacts of mothers having greater access to paid parental leave through their employment, and mothers choosing to delay the commencement of PLP to start once this leave entitlement is exhausted.

These findings are consistent with the overall patterns by child age, showing increased proportions of mothers using PLP when their children are between 5 and 11 months old (see Figure 1).

Figure 6: In recent years around 2 in 5 mothers are starting PLP after the first 2 months

Months since first day of birth month to start date of PLP, by financial year of PLP commencement

Note: Timing of commencement is an approximation. While date of start on PLP is known, day of month of birth is not known.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023

Multivariate analysis of who starts PLP early

While the timing of commencement of PLP is likely strongly related to employment factors, here we have presented some findings from analysis of how timing of commencement varies with a range of available demographic variables. These do not include employment variables, as this information is not available in the DOMINO data.24

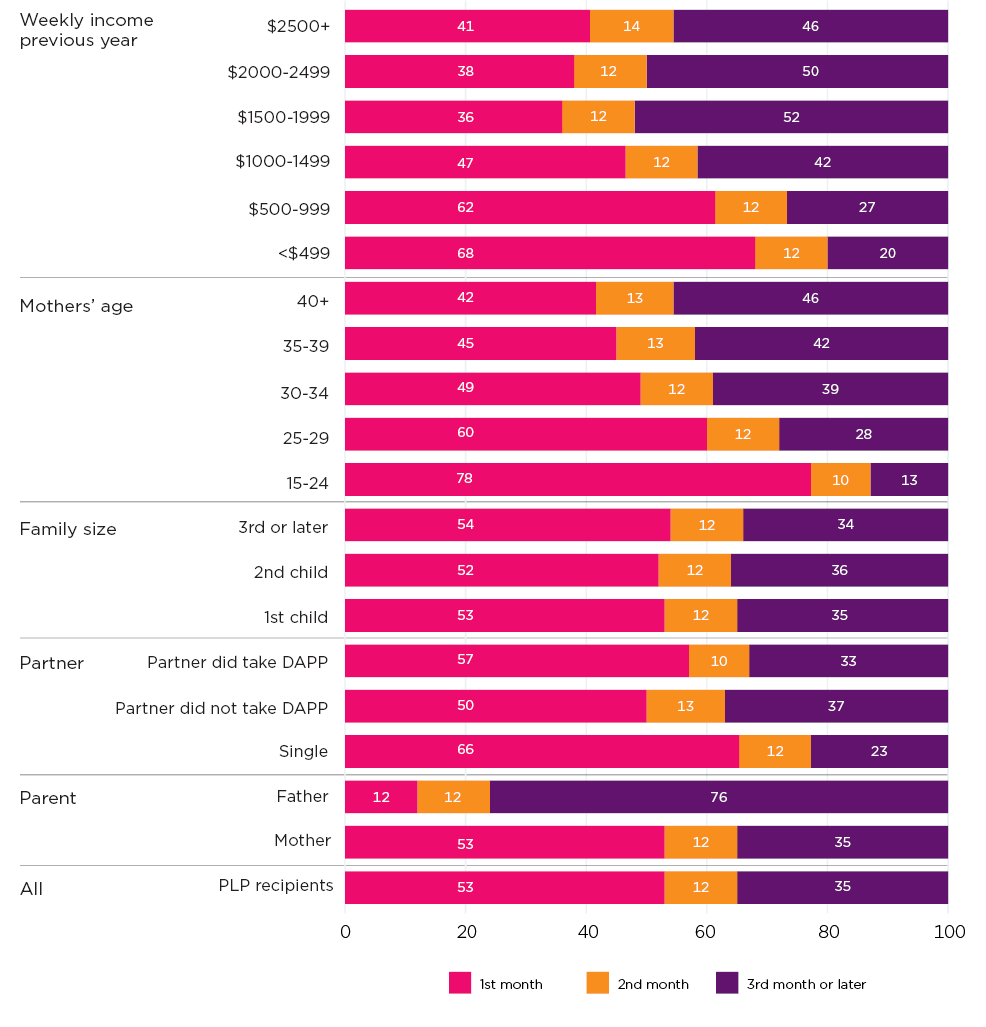

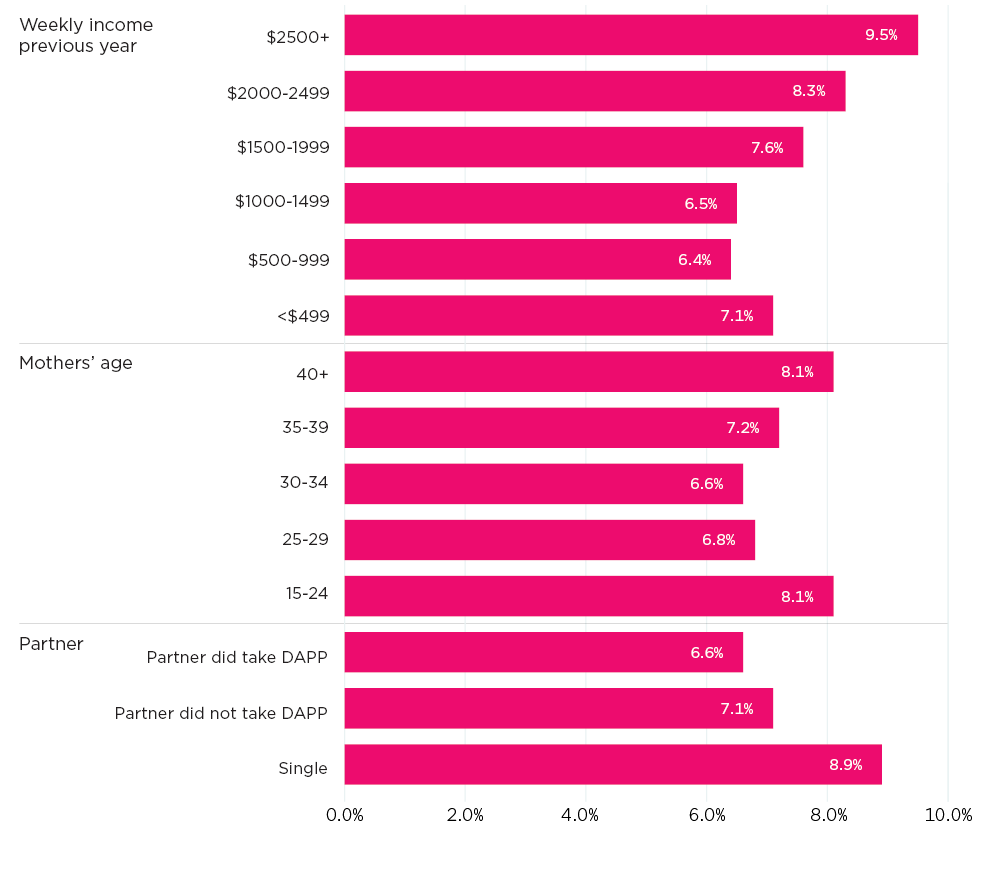

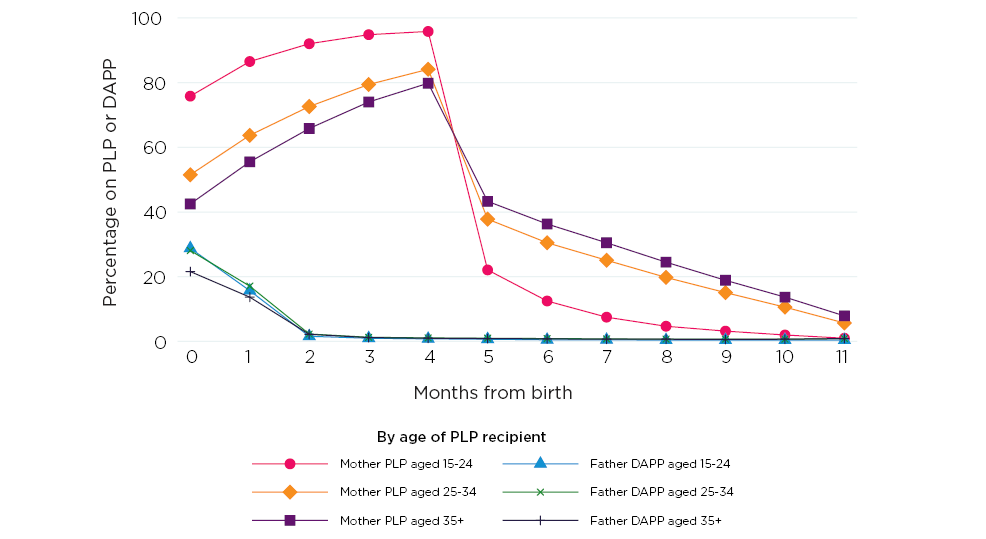

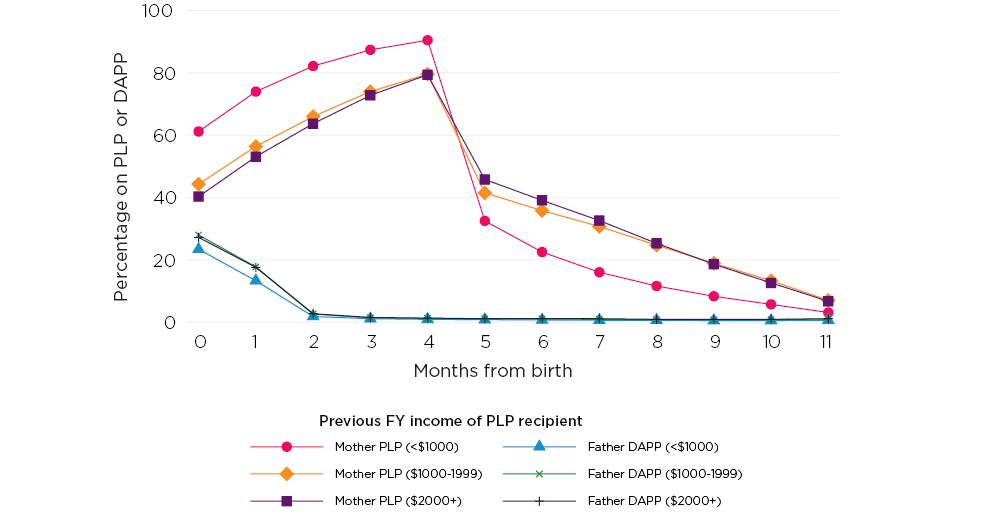

Selected predicted values, showing three broad categories of timing of commencement, are shown in Figure 7. Focusing on the likelihood of starting early:

- Those with the lowest incomes before the birth are the most likely to start early. This includes those with weekly income before the birth of up to $1,500 (inflation-adjusted), with less variation between income bands once income is more than this.

- The youngest mothers (aged 15-24 years) are the most likely to start PLP in the first month, with the likelihood of starting early decreasing with each older age group.

- Single mothers are most likely to start PLP in the first month.

- Noting that some fathers share in the PLP, fathers' PLP start time is much more likely to be later compared to mothers using PLP.

While not shown as predicted values in Figure 7, there were also significant findings for other variables (see the multivariate results in Appendix Table 9). Starting early was more likely if overseas-born, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and if the child was not one of a multiple birth. There were some differences by remoteness and across states and territories.

Starting PLP early is likely to be an indicator of having no paid parental leave through employment, so the findings related to low income, young mothers and single parenthood are expected to reflect these mothers having been more often working in jobs without paid leave entitlements. Timing of PLP use is examined further later, when looking at this from the child's perspective (see Child-level perspectives in section 7).

Figure 7: Young mothers, single mothers and those with lowest (previous year) incomes are most likely to start PLP early

Predicted values from multivariate analysis of timing of PLP start

Notes: Timing of commencement is an approximation. While date of start on PLP is known, day of month of birth is not known. Full multivariate results are in Appendix Table 9. Predicted values are calculated following multinomial logistic regression that also includes state, remoteness, financial year, whether Australian-born, whether Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, family size, whether one of multiple birth. Predictions are done over the full population of PLP recipients up to those starting in 2020-2021. Later data were excluded due to the extent of missing income and geographic information after this time. Income was adjusted by CPI to be in 2020-21 dollars.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023

DAPP commencement

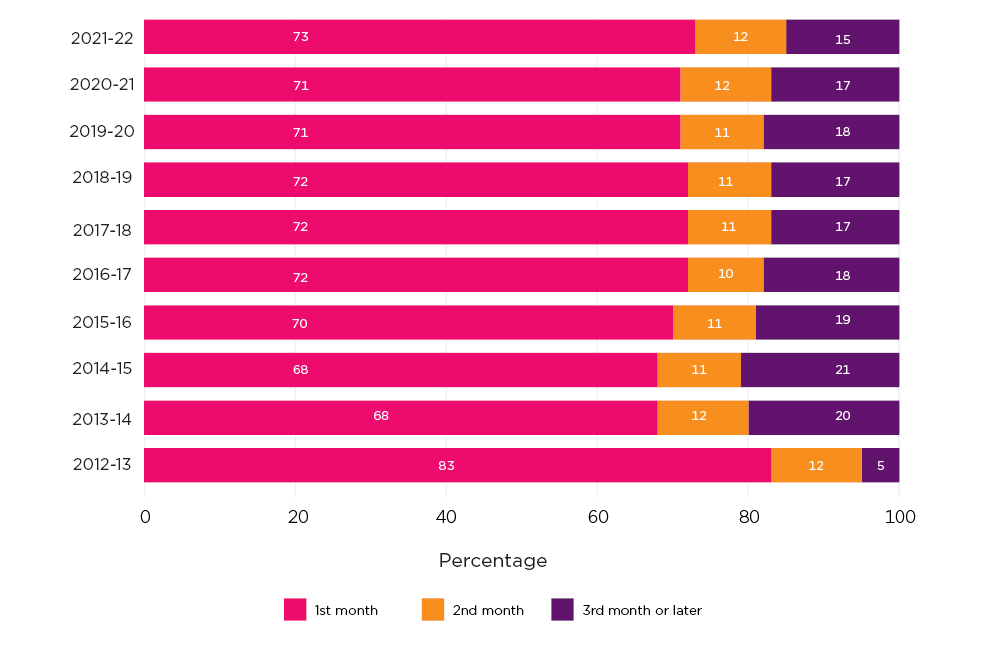

Across 2012-13 to 2021-22, the median timing of DAPP commencement was within the first month after the child's birth. While this did not vary over the financial years, Figure 8 shows a slight increase in the proportion taking it within the first month.

Figure 8: More than two in three fathers started DAPP in the first month

Months since first day of birth month to start date of DAPP, by financial year of DAPP commencement

Note: Timing of commencement is an approximation. While date of start on DAPP is known, day of month of birth is not known.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023

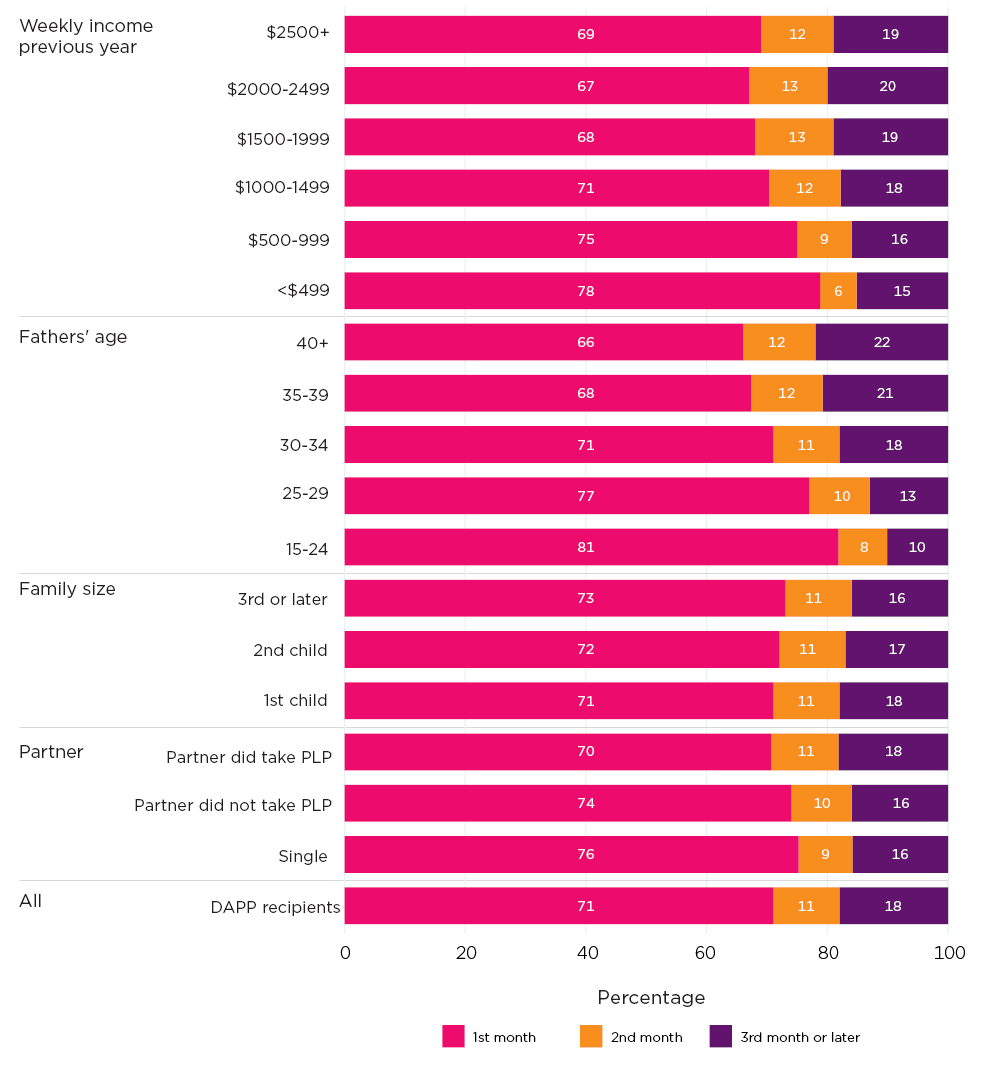

Multivariate analysis was used to see what factors were associated with starting DAPP at different times. Selected findings are presented as predicted values in Figure 9 (with model estimates in Appendix Table 10).

- Fathers with the lowest incomes were the most likely to have started DAPP in the first month after the birth

- Younger fathers were most likely to start in the first month. With increased age, fathers were more likely to start DAPP later.

Figure 9: Early DAPP commencement was most likely for young fathers and fathers with lowest (previous year) incomes.

Predicted values from multivariate analysis of DAPP start time

Notes: Timing of commencement is an approximation. While date of start on DAPP is known, day of month of birth is not known. Full multivariate results are in Appendix Table 10. Predicted values are calculated following multinomial logistic regression that also includes State, remoteness, financial year. Predictions are done over the full population of DAPP recipients up to those starting in 2020-21. Later data were excluded due to missing income and geographic information. Income was adjusted by CPI to be in 2020-21 dollars.

Source: PLIDA, DOMINO data update March 2023

6.2 Length of time on PLP or DAPP

PLP

The design of PLP allows for 18 weeks of payment. The vast majority of PLP recipients use all 18 weeks, rather than using less than this, such as by returning to work or transferring PLP to another parent (Table 4). With the introduction of Flexible PLP in July 2020, parents can use an initial block of 12 weeks, then use the remaining 6 weeks flexibly up until the child's second birthday. This has had the effect of increasing the elapsed time from start to end of some parents' PLP, explaining the percentage in Table 4 with apparently more than 18 weeks of PLP (7-8% of recipients).25

| Up to 17 weeks (%) | 18 weeks (%) | >18 weeks (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 1.9 | 98.1 | - | 100.0 |

| 2011-12 | 2.4 | 97.6 | - | 100.0 |

| 2012-13 | 2.6 | 97.4 | - | 100.0 |

| 2013-14 | 3.1 | 96.9 | - | 100.0 |

| 2014-15 | 3.4 | 96.6 | - | 100.0 |

| 2015-16 | 3.4 | 96.6 | - | 100.0 |

| 2016-17 | 3.3 | 96.7 | - | 100.0 |

| 2017-18 | 3.5 | 96.5 | - | 100.0 |

| 2018-19 | 3.5 | 96.5 | - | 100.0 |

| 2019-20 | 3.5 | 96.5 | - | 100.0 |

| 2020-21 | 3.1 | 89.9 | 7.0 | 100.0 |

| 2021-22 | 1.6 | 90.0 | 8.4 | 100.0 |